Remembrance of Noble Actions

TheDilemma

To Support Revolution?

Native Americans

"You know we are Americans; that is our native country"

The "chiefs, sachems and young men of the River St. John's" to the British Commanding officer, explaining their intention to fight alongside the Americans, August 1778.

Portrait of Guy Johnson and Karonghyontye, Benjamin West. Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington. (above)

This portrait of Guy Johnson, British Superintendent of Indian Affairs of the Northern Department, and Karonghyontye (also known as David Hill) was painted in England in 1776. Johnson’s nephew Sir William Johnson, who had served in the same position and in 1759, married Molly Brant, sister of Joseph Brant, an influential Mohawk leader. Brant used his influence to persuade the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Confederacy) to fight for the British. This ultimately came in 1777, when Clan Mothers accepted British promises to maintain supply lines to the nations. Formal nation-level agreements aside, Native towns were often divided in their loyalties, nearly half of Oneidas sided with the British, Tuscaroras and some Onondagas and Mohawks supported the Americans.

The decision to fight for America against the English was a difficult one regardless of social rank or ethnic background. For the Native American nations, and for enslaved African Americans, it was especially problematic. In the two centuries of European presence in North America, Indigenous people had their land taken and occupied by colonists, moving inexorably in all directions. Earlier in the 18th century, during the French and Indian War (1754-1763), some Native nations joined with the French in an effort to eject the English from their land. Now just two decades later, the colonists, the ones living on and using that land, were fighting the English.

Many Native nations were divided, and long-term alliances severed by the choices they made.

Many Indigenous nations tried to remain neutral. Others calculated that their best future lay with the British. By 1775, colonists had pushed many people from their homelands along the east coast taking land Native Americans had lived on, farmed, and hunted on for thousands of years. A number of factors led some Native nations to side with the British, not the least of which were the various treaty alliances made over the years. Some Native people however, cast their lot with the colonists after their old allies, the French, entered the conflict on the American side. Native people became divided, and long-term alliances severed by the choices they made.

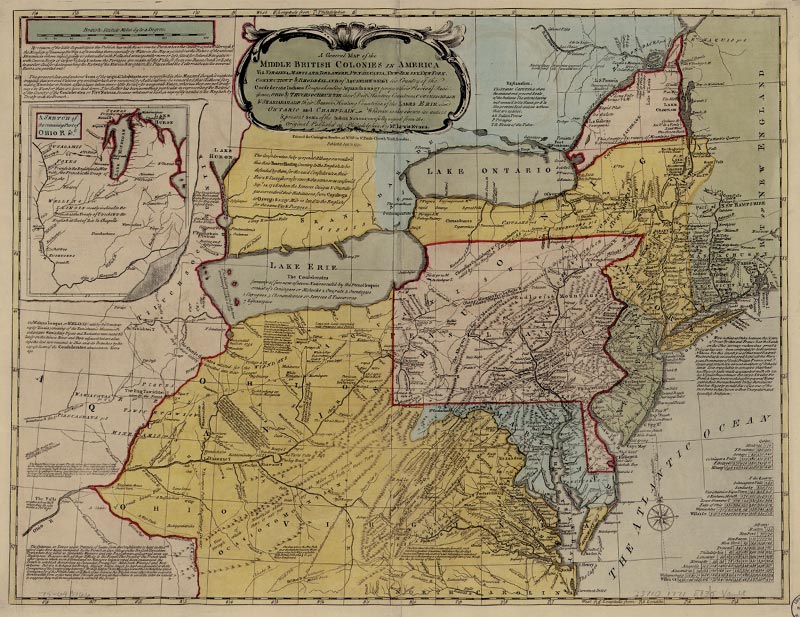

A General Map of the Middle British Colonies in America, Lewis Evans, printed in 1771 by Carington Bowles. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division. This map of eight of the British colonies shows the locations of several tribes of American Indians.

John Scesux Engraved Powder Horn, 1750-1785. DAR Museum Collection

Some Native Americans had no other choice than to side with the colonists. Although they were pacifists, John Scesux and other members of the Christian Brotherton community of Rhode Island were forced to prove their loyalty to the colonists or risk death and further displacement. The Brotherton community was comprised of displaced Native Americans of Algonquian roots who converted to Christianity from the New England area. Scesux mustered into Captain John Babcock’s Company in the Rhode Island Regiment of Battalion in March of 1778, to serve one year. After serving as a patriot in the American Revolution, John Scesux served the Brotherton Community as a trustee. He died in 1807 after the community relocated to New York. Eventually, the entire community was forced to relocate again to Wisconsin.

Further north, some in the Wabanaki Alliance, a confederacy of nations somewhat like the Haudenosaunee, supported the British while others pledged support to the revolutionaries. Former loyalties and alliances with the French may have helped make the decision easier and some, in light of economic or personal reasons, decided it was more beneficial to work with both sides. In November 1779, at Machias, Maine, Pierre Tomah a Malecite chief, explained his decision to support the Americans:

We have now risen from our Beds and left our former place of abode and come and join you for the regard we have for America and the King of France. I hope by the blessing of God that we shall be preserved through all our Difficulties whether or not we shall be able to go through by the Assistance you will afford us.

He asked the Americans to support his people against certain retribution from his fellow Abenakis and the English. Later, when it became unclear whether the Americans could protect them, and citing his people’s need of food and other necessities, he met with British officials from Nova Scotia who promised both.

African Americans

"Liberty is equally as precious to a Black man, as it is to a white one, and Bondage Equally as intollarable [sic] to the one as it is to the other"

Lemuel Haynes, "Liberty Further Extended : Or Free Thoughts on the Illegality of Slave-keeping" c. 1776

As the Revolution neared, free Black Americans had a choice similar to their white counterparts — to remain loyal to the Crown, to support the cause of independence, or to not take sides at all. For enslaved Black people, the circumstances were more complex, and especially ironic. Should they help white Americans fight for their liberty — a liberty they did not share? English overtures promised enslaved people freedom if they ran away to the British army, a scenario especially feared by enslavers. Self-liberation, if they were close enough to reach the British, meant leaving family behind and if the Americans won their fight for independence, what would happen then?

Many enslaved men sought to earn their freedom by serving in their enslaver’s place.

At the beginning of the Revolutionary War, most states expressly prohibited the enlistment of Black men regardless of their status. The idea of giving weapons to men who might well be tempted to use them against their oppressors frightened many white people. As time progressed, and the need for soldiers became more desperate, state after state set in place systems by which enslaved Black men could earn their freedom by serving in the military. Some could serve as a substitute, in place of someone else, with the promise of emancipation at the end of the war; many took advantage of this.

When one considers the situations in which Black civilians found themselves during the 1770s, supporting the Revolution was not a given.

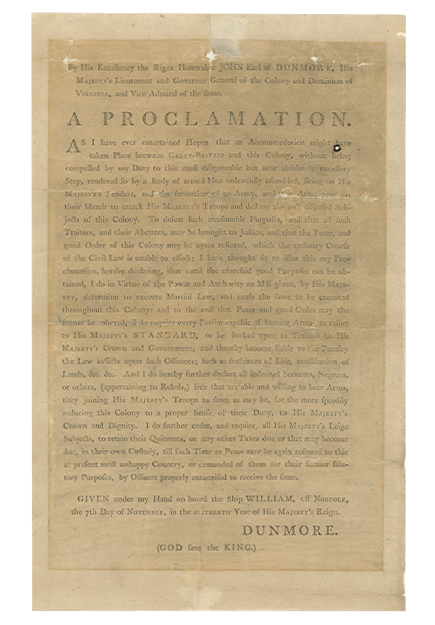

Reproduction of Dunmore’s proclamation. Courtesy of the Library of Virginia.

In November 1775, Virginia’s royal governor Lord Dunmore offered freedom to enslaved men who would join him in fighting the colonists. Dunmore’s Proclamation declared martial law and invited those enslaved by the rebellious Americans (not those of loyalists) to join him: “And I do hereby further declare all indented [sic] Servants, Negroes, or others, (appertaining to Rebels,) free that are able and willing to bear Arms, they joining His MAJESTY’S Troops as soon as may be.” Word quickly spread, and, although estimates of the total numbers differ, at least 400 enslaved men joined Dunmore’s troops. Some of these men formed Dunmore’s “Ethiopian Regiment,” outfitted with uniforms emblazoned with the motto “Liberty to Slaves.”

Some enslaved men sought to earn their freedom by serving as a substitute.

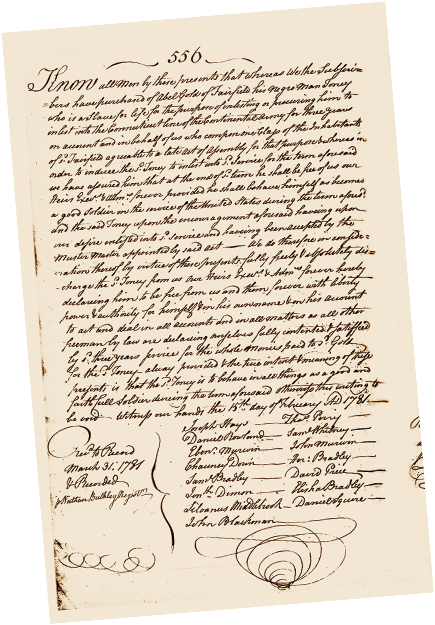

Document describing Connecticut slave Toney as a substitute. Courtesy of Fairfield Archives, Fairfield, CT.

In this document, fifteen citizens of Fairfield, Connecticut, attest that they purchased an enslaved man named Toney from Abel Gold, for the purpose of having him serve in the Continental Army. For this service, they promised him his freedom. Having been accepted by the Muster Master, Toney is now free “from us, our Heirs, . . . forever” — that is providing that Toney remains a “good and faithfull soldier.” Otherwise, “this writing be void.” Toney’s choice to remain in the army was not his own; the document required him to serve for a minimum of three years or be forced back into slavery.

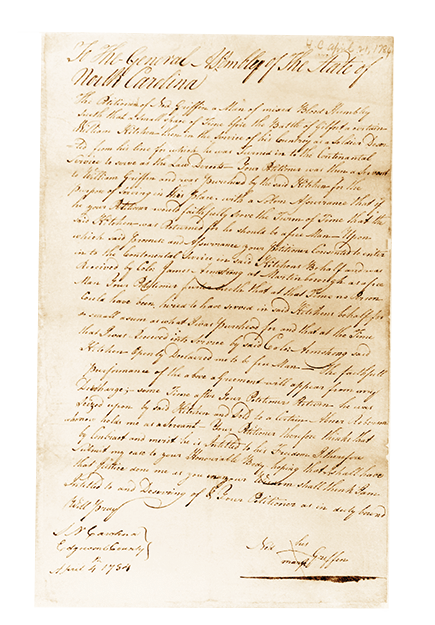

Ned Griffin’s Petition to the General Assembly of North Carolina, April 21, 1784. Courtesy of the State Archives of North Carolina Office.

In North Carolina, Edwin (Ned) Griffin, served in place of his owner, William Kitchen, in exchange for his freedom. Kitchen purchased Griffin from his previous enslaver for the sole purpose of using him as a substitute in the Continental Army. At war’s end, Griffin was not emancipated and had to sue for his freedom. In this document, Ned Griffin outlines the circumstances of his enlistment, and states that, contrary to the agreement made in 1781, at war’s end his owner William Kitchen sold him to “a certain Abner Roberson.” Griffin appeals to the legislature, “hoping that I shall have that Justice done me as you in your Wisdom shall think I am Intitled to.” The General Assembly freed Ned Griffin later that year, by an Act of Emancipation.