Remembrance of Noble Actions

Native American

Patriots

Click on a name below to read more about each patriot.

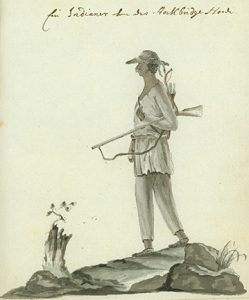

Mohican Indian in Stockbridge militia at White Plains, NY, watercolor sketch, 1778 from Johann von Ewald Diary. Reproduction Courtesy Bloomsburg University, Andruss Library Special Collections, the Joseph Tustin Papers.

Hessian officer Johann von Ewald drew this sketch of a scout from Stockbridge, Massachusetts, serving in a militia unit under the command of Mohican Abraham Nimham, and encamped in 1778 at White Plains and the Bronx, New York. The sketch was done just before the skirmish with British Colonel John Simcoe’s Rangers during which as many as twenty Mohican patriots were killed, including Abraham Nimham and his father.

The Battle of Oriskany. Newspaper account from the Pennsylvania Journal and the Weekly Advertiser, September 3, 1777. Courtesy of the Library Company of Philadelphia.

The Battle of Oriskany. Newspaper account from the Pennsylvania Journal and the Weekly Advertiser, September 3, 1777. Courtesy of the Library Company of Philadelphia.

This account of the battle between “General Harkeman [sic] and the enemy at Oneyda Creek” describes the actions of a “friendly Indian” and his family who killed a large number of British soldiers. After the unnamed “Indian” was shot through the wrist, his wife, on horseback, fought by his side “with pistols.” Oneida oral tradition recounts that this unnamed Native American was Hanyere, Oneida leader and long-time foe of the British ally, Joseph Brant.

Although the Battle of Oriskany was not a clear-cut victory for either side, it forced the British General Barry St. Leger to retreat and prevented his troops from reaching Saratoga. In retaliation for the Oneida’s support of the Americans during the Battle of Oriskany, Mohawks allied with the British destroyed the Oneida village of Oriska.

George Washington, an enslaver, had mixed feelings about employing enslaved people in the military. He considered it an advantage however, to have Native Americans fighting on his side. In a letter of July 4, 1776, he wrote to Congress that he thought it:

“advisable to take measures to engage those [Native Americans] of the Eastward, the St. Johns, Nova Scotia, Penobscot &ca. in our favor. I have been told that several might be got, perhaps five or six hundred or more, readily to Join us. If they can, I should imagine, It ought to be done. It will prevent our Enemies from securing their friendship, and further, they will be of infinite service, in annoying and harrassing them should they ever attempt to penetrate the Country. “

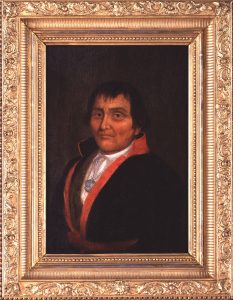

John Neptune, portrait by Obadiah Dickenson. Portrait of Penobscot Lieutenant Governor John Neptune (1836) Collections of the Maine State Museum (#79.40.283).

John Neptune, portrait by Obadiah Dickenson. Portrait of Penobscot Lieutenant Governor John Neptune (1836) Collections of the Maine State Museum (#79.40.283).

When his portrait was painted in 1836, John Neptune was a Lieutenant Governor of the Penobscots. During the American Revolution, he was one of many Penobscot men who fought for the Americans, helping defend Maine’s frontier from British incursions from Canada.

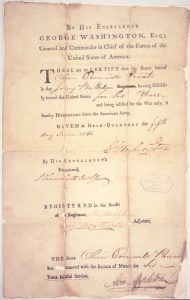

Honorable discharge of Oliver Cromwell. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.

Honorable discharge of Oliver Cromwell. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.

Oliver Cromwell of Columbus, New Jersey, served over six years in the Continental Army. He participated in the now famous Washington’s crossing of the Delaware River, the Battle of Monmouth Court House, and at the Battle of the Brandywine. George Washington signed his honorable discharge from the army. Records relating to Cromwell’s history, describe him variously as Black, mulatto, and Indian. Listing people by various racial and ethnic identities was common in the 18th and early 19th centuries.

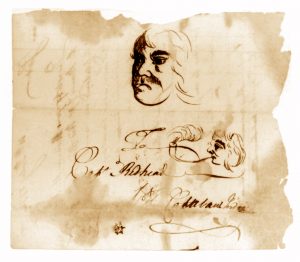

Drawing of Catawba Indian. Courtesy of the South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC

Drawing of Catawba Indian. Courtesy of the South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC

The Catawba Nation of the Carolinas after having much of their land taken from them by white settlers, had come to depend on the colonial government for protection against their enemies, the Cherokee and the Haudenosaunee. Catawba warriors fought alongside the English during the French and Indian War. This drawing from the period of the American Revolution is of a Catawba warrior identified as “Captain Redhead.” There are at least two men named “Readhead” listed as American soldiers from the Catawba Nation.

After Independence, Life Following the Revolution

“I fought against the British for your sake, the British have disappeared, and you are free, yet from me the British took nothing, nor have I gained any thing by their defeat.”

Peter Harris, Catawba warrior, in his pension application of 1822.

Receipt for blankets and clothing with list of Oneidas. Courtesy of the New York State Archives. New York (State). Comptroller’s Office. Selected audited accounts of state civil and military officers, 1780-1858. Series A0802-78, Volume 15, p. 70b..

Receipt for blankets and clothing with list of Oneidas. Courtesy of the New York State Archives. New York (State). Comptroller’s Office. Selected audited accounts of state civil and military officers, 1780-1858. Series A0802-78, Volume 15, p. 70b..

In 1792, a group of Oneidas received “fifty blankets and two suits of Indian clothing” as a gratuity for special services during the American Revolution. The names of twenty-two warriors are affixed to the document, along with their marks

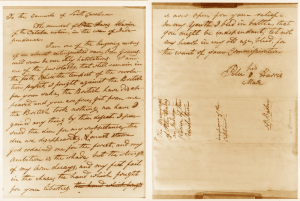

Peter Harris pension request. Courtesy of the South Carolina Department of Archives

Peter Harris was a member of the Catawba nation who fought with the colonists in the American Revolution. In his old age, he eloquently petitioned the government of South Carolina for a pension. “. . . the strength of my arm decays, and my feet fail in the chase, the hand which fought for your liberties, is now open for your relief. In my youth, I bled in battle, that you might be independent, let not my heart in my old age, bleed, for the want of your Consideration.”

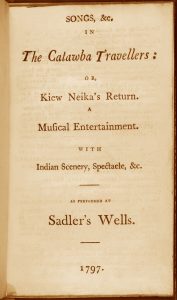

Songs &c. in The Catawba Travellers, title page. Courtesy of New York Public Library.

Songs &c. in The Catawba Travellers, title page. Courtesy of New York Public Library.

During the 1790s, Peter Harris and three other Catawbas traveled to England where they toured and made theatrical appearances. It is probable that Harris performed this “Musical Entertainment,” with references to Native American customs and practices.

Legacy

The legacy of the American Revolution is as complex and filled with contradictions as the people who lived through it. The traditional narrative of the evil red coats and the heroic patriots fighting for freedom is far more nuanced when looking at the objects, stories, lives, and perspectives of the people who were actually there. The same people who yelled “we will not be slaves to England” held thousands of Black people in bondage and stole Native lands. Many of the leaders of the Revolution fighting for their own freedom denied it to others. Yet some of the Native Americans and Black people who sided with the patriot cause saw hope in the words of the Revolution. Those words would allow for generations of people to chip away at the nation’s foundation of white supremacy. Each generation of Americans pushes the United States closer to the ideals of the Revolution.

Nancy Ward (Nanye’hi) was a Cherokee woman who warned nearby settlers of an impending attack by the British and her nation. She also supplied Americans with milk and beef, defying most Cherokees who sided with the British. At least sixty-six women have joined the National Society Daughters of the American Revolution using Nancy Ward as their patriot ancestor. A DAR chapter in Tennessee is named for her.