Remembrance

of Noble Actions

African Americans and Native Americans in the Revolutionary War

"Obscurity in life and oblivion is too often the lot of the worthy – they pass away, and no 'storied stone' perpetuates the remembrance of the noble actions."

Free Press, Norristown, Pennsylvania, January 15, 1834 Obituary of Edward Hector, Black private, Captain Hercules Courtney’s Company, 3rd Pennsylvania Artillery, Continental Line

Excluded from

the Narrative

For nearly 250 years the face of the American Revolutionary patriot has been represented as a white man. The reality is patriot forces came from all walks of life, backgrounds, races, ethnicities, and religions. The years after the American Revolution saw some of these patriots recognized for their service, sometimes in due course but often after petitioning state and federal governments. As the revolutionary generation dwindled in the 19th century, efforts to record their experiences in books, pamphlets, and newspaper articles took on a new urgency. Nevertheless, the exploits of Black and Native American patriots were segregated from the larger narrative of American independence and eventually overshadowed altogether. This exhibit is an effort to illuminate some of those stories so that they may be included once again in the American Revolutionary epic.

Identity

The actual number of patriots of color is undoubtedly larger; recognizing them can be difficult. Very few military muster rolls identify soldiers by race or by any type of physical description. Over two hundred years in the evolution of the English language challenges researchers. If an 18th century record identifies someone as having a “ruddy,” “brown,” or “black” complexion, did that mean the same thing in 1776 as it does today?

Descriptors used in the period, “Negro,” “mulatto,” “colored,” “free man of color,” or “Indian” to describe people who are not identified as white do not always appear in military or other records. The terms themselves are not consistent either; a person described as mulatto could refer to a dark-skinned person regardless of any relatives of African descent. Names can sometimes offer clues. Prince, Caesar, and Cuffee were common names for Black men in early America. Enslaved people were often listed by one name only, or a first name followed by a descriptor, such as “Negro.” Reliance on names alone is tricky. For instance, Caesar Jackson was a Black soldier from Maine. Caesar Rodney was a white government official, member of the Continental Congress from Delaware, and a signer of the Declaration of Independence. Another man named Africa Hamlin from Massachusetts had in the past been identified as a likely Black Revolutionary War soldier, he turned out to be white with siblings named Europe, Asia, and America. Native American names seem to be easily identifiable, yet many are listed in records with English or French names.

Clues from the Records

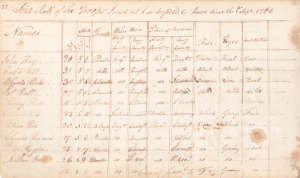

Page from “Chesterfield supplement”. Courtesy of the Library of Virginia

What do the many records that survive from the period of the American Revolution tell us about the women and men who participated in the conflict?

Though most official military records make scant reference to physical appearance of soldiers, there are a few documents that do. Size rolls, while primarily meant to list soldiers’ heights, sometimes include descriptions of hair, eyes, and skin color. Among the more remarkable of these is the so-called “Chesterfield supplement,” delineating the physical attributes as well as the birthplaces of the enlistees.

All enlisted soldiers, regardless of race or ethnicity, were to receive pay for their services, as well as “bounty” — cash, land, and clothing. George Washington, in a letter written in December 1779, suggested that,

“There being no arrangements formed for recruiting in the country, and the State bounties for short services so greatly exceeding the Continental, as to afford small prospect of success in such attempts, all I can do is to recommend to your best endeavours the re inlisting[sic] those men whose times of service are nearly expiring before their leaving the regiment, upon such encouragement as is allowed by Congress; that is to every soldier, or man reinlisting[sic] for the war a bounty of 200 Dollars, and a gratuity to the officer of ten.”

In 1780, when Congress awarded a major’s commission to Abenaki leader Joseph Louis Gill, it stipulated that the men in his company were to receive “the like pay Subsistence & Rations with the officers and Soldiers of the Continental Army.”