Remembrance of Noble Actions

African American

Patriots

Click on a name below to read more about each patriot.

George Washington by John Trumbull. Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Charles Allen Munn, 1924

George Washington by John Trumbull. Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Charles Allen Munn, 1924

In 1780, artist John Trumbull painted George Washington accompanied by an enslaved, liveried servant wearing a turban. Historians believe this young man is William Lee, the General’s valet. In his will, Washington arranged to free Lee, “or if he should prefer it (on account of the accidents which have befallen him and which have rendered him incapable of walking or of any active employment) to remain in the situation he now is, it shall be optional in him to do so. In either case, however, I allow him an annuity of thirty dollars during his natural life . . . and this I give him as a testimony of my sense of his attachment to me and for his faithful services during the Revolutionary War”

Lee lived out his life at Mt.Vernon, and was buried in the slave cemetery there.

The Washington Family, Edward Savage. Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington.

Some free Black people chose to remain loyal to the Crown, and at war’s end many Black loyalists moved to Canada.

Black people who sided with the revolutionaries could serve in the military or use their skills and talents to provide goods and services needed by the Continental Army.

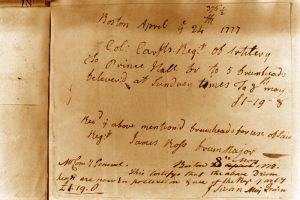

Bill of Sale for drumheads, Prince Hall. Courtesy of the Massachusetts State Archives

Bill of Sale for drumheads, Prince Hall. Courtesy of the Massachusetts State Archives

Prince Hall was a formerly enslaved man who worked as a leather dresser. In 1777, he billed Col. Thomas Crafts’ regiment of artillery for drumheads he supplied. James Ross, drum major of that regiment, signed the invoice.

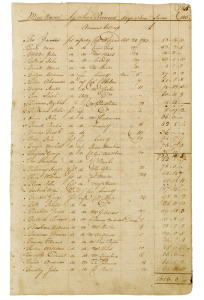

Page from Virginia Auditor of Public Accounts Entry 218, Revolutionary War Service Page, List of Officers who Received Certificates.” Courtesy of The Library of Virginia

Page from Virginia Auditor of Public Accounts Entry 218, Revolutionary War Service Page, List of Officers who Received Certificates.” Courtesy of The Library of Virginia

This page from the Virginia State Auditor’s accounts shows that a Colonel Newton received a certificate for William Flora’s service during the Revolution, presumably to be given to Flora. When hostilities began, William Flora joined a local militia and fought valiantly at the Battle of Great Bridge outside Norfolk on Dec. 9, 1775. Later he joined the 15th Virginia Regiment and served to the war’s end.

Flora received a badge of merit when he was discharged in 1783. In 1806, he was awarded 100-acre land bounty for his heroic service at Great Bridge and in 1818, Flora received a veteran’s pension.

“A List of the Names of the Provincials who were Killed and Wounded”. Courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society.

From the beginning of the Revolutionary War, men of color fought for the American cause. This undated broadside lists the names of those killed and wounded at Lexington and Concord, April 19, 1775. Among the wounded is “Prince Easterbrooks (A Negro Man).” Easterbrook went on to serve eight years in the militia and Continental Army. Upon dissolution of the Continental Army, Easterbrook returned to Lexington.

Lafayette at Yorktown by Jean-Baptiste Le Paon, 1783. Courtesy of Lafayette College Art Collection, Gift of Helen Fahnstock Hubbard in Memory of her husband, John Hubbard.The Black man in this portrait of the Marquis de Lafayette is believed to be James Armistead, who later took the last name Lafayette. He was an enslaved man from New Kent County, Virginia, who served Lafayette as a double agent in the camps of British Generals Benedict Arnold and Charles Cornwallis, near Portsmouth and Yorktown, Virginia.

Certificate by Lafayette commending James Armistead Lafayette’s service. Reproduction courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical SocietyBefore leaving America in 1784 the Marquis de Lafayette wrote a certificate for James (not yet known as Lafayette), commending him for his work as a spy. James had secured a position as Cornwallis’ servant and sent information to Lafayette concerning the British troop strength and plans.

“A correspondant of mine, servant to Lord Cornwallis, writes on the 26th July at Portsmouth, and says His Master, Tarleton and Simcoe are still in town but expect to move. The greatest part of the army is embarked. There is in Hampton Road one 50 guns ship, and two six and thirty guns frigates [ ] 18 sloops loaded with horses. There Remain But nine vessels in Portsmouth who appear to be getting ready.” Lafayette to Washington, July 31, 1781, referring to James.

The certificate reads:

“This is to certify that the bearer by the name of James has done essential services to me while I had the honour to command in this State. His intelligences from the enemy’s camp were industriously collected and more faithfully delivered. He properly acquitted himself with some important communications I gave him and appears to be entitled to every reward his situation can admit of. Done under my hand, Richmond, November 21st, 1784. LaFayette”

Two years later, the General Assembly of Virginia emancipated James, citing his service in the war. Later, James Armistead Lafayette received a pension of sixty dollars.

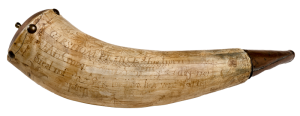

Powder horn carved by Garshom Prince, 1761. Courtesy of the Courtesy of the Luzerne County Historical Society

It is unclear whether Garshom (or Gershom) Prince was enslaved by or a hired servant of Captain Robert Durkee. The inscriptions on his powder horn indicate that he fought during the French and Indian War as well as in the American Revolution. He was killed at the Battle of Wyoming in Pennsylvania in 1778, along with Durkee. He carved this powder horn during the French and Indian War and made inscriptions and engravings on it, including when, where, and for whom (himself) he made the horn.

Bucks of America regimental flag, silk, 1776-1780. Courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society

The Bucks of America was an all-Black militia company from Massachusetts probably led by African American Colonel George Middleton. They do not appear in any official military records of the war and little is known of their service. The regiment received this flag from Governor John Hancock, at a ceremony in Boston near the end of the American Revolution. The flag has 13 stars for the colonies, a buck, and pine tree as symbols of their regiment.

Bucks of America Badge, medallion, 1776-1780. Courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society

Bucks of America regiment members received and wore this badge inscribed with their initials (for example the “M.W.” on this one).

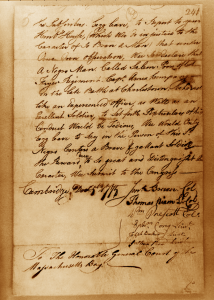

Recommendation of Salem Poor for bravery. Courtesy of the Massachusetts State Archives

After Salem Poor’s service during the Battle of Bunker Hill where he reportedly killed British Lieutenant Colonel James Abercrombie, fourteen officers signed this document. Poor was a Black man from Massachusetts who also served at the Battle of White Plains and endured the crushing winter of 1777-78 at Valley Forge.

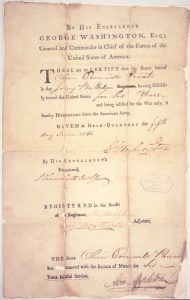

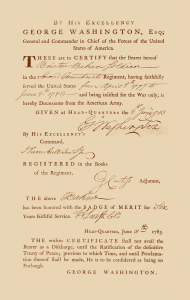

Honorable discharge of Oliver Cromwell. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.

Oliver Cromwell of Columbus, New Jersey, served over six years in the Continental Army. He participated in the now famous Washington’s crossing of the Delaware River, the Battle of Monmouth Court House, and at the Battle of the Brandywine. George Washington signed his honorable discharge from the army. Records relating to Cromwell’s history, describe him variously as Black, mulatto, and Indian. Listing people by various racial and ethnic identities was common in the 18th and early 19th centuries.

Rhode Island furnished more than its share of regiments to the American Revolution. By 1777, more than half of the eligible men in the state had enlisted. George Washington called for another battalion from Rhode Island but from where were the men to come? General James Varnum suggested a radical solution to the problem: a battalion of enslaved people. The Rhode Island Assembly passed a resolution allowing that “every able-bodied Negro, mulatto, or Indian man slave” could enlist, receive the same bounties, and wages as other soldiers – and receive their freedom.

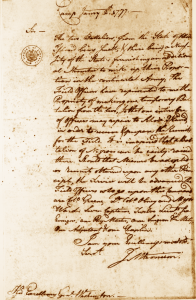

Letter from [J.] M. Varnum to George Washington, 2 January 1777. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, George Washington papers.

In his letter, General James Varnum, a Rhode Island lawyer prior to the war, proposed combining the two Rhode Island regiments and included a Black battalion. “It is imagined that a Battalion of Negroes can be easily raised there.” He named Colonel Christopher Greene and Lieutenant Colonel Jeremiah Olney as the “field officers” to command the unit.

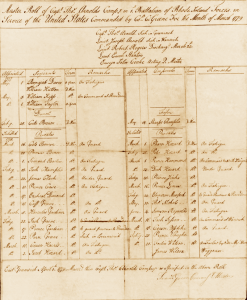

Muster Roll of Capt. Thomas Arnold Camp for 1st Battalion of Rhode Island Forces in Service of the United States Commanded by Col. Christopher Greene. Courtesy of the Rhode Island Historical Society, Providence, Francis Green. Muster Roll of Captain Theodore Arnolds – Month of March 1779, East Greemwich, RI. April 1, 1779; ink on paper manuscript, MSS 673 B6 F29

This muster roll for the month of March 1779, lists the names of the members of an all-Black battalion.

The regiment went on to participate in the Battle of Long Island, Battle of Red Bank, Battle of Rhode Island, Battle of Pines Bridge, and the Siege of Yorktown to name a few.

Discharge Certificate for Brister Baker

Brister (or Bristol) Baker, a Black man, was a member of 2nd Connecticut Regiment during the American Revolution. George Washington signed his honorable discharge certificate. In 1855, William Cooper Nell reproduced the certificate in his book, Colored Patriots of the American Revolution.

Pewter plate. Courtesy of Revolutionary Spaces.

This 18th-century pewter plate (one of a three-piece set) belonged to Jeffery Hartwell (Jesse Freeman), a Black soldier from Bedford, Massachusetts. He entered the local militia as the substitute for his enslaver, Joseph Hartwell. He later served in a number of Massachusetts regiments until discharged in 1779.

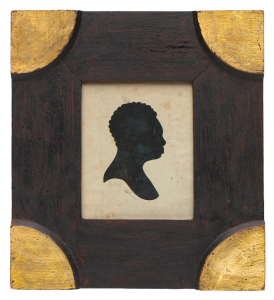

Hollow-cut of Prince Simbo. DAR Museum Collection

By all indications, Prince Simbo was a free African American when he enlisted in Captain Ebenezer Hills’s Company of the 7th Connecticut Regiment at Valley Forge on February 23, 1778. Simbo’s enlistment term was three years before he could either re-enlist or retire from service. Simbo first saw major action with the 7th Connecticut Regiment at the Battle of Monmouth in June of 1778. The years 1779 and 1780 were not as kind to Simbo. According to the March muster roll, Simbo was “sick and in Glastonbury.” He was then furloughed in December 1780 by Colonel Philip Bradley for 30 days. It is unclear what happened to Simbo to warrant this furlough, but that it resulted in injury is clear: he was transferred to the care of the Corp of Invalids on October 4, 1780. A report from the Invalid Corp notes that Simbo was unfit for duty due to “Rhumetism and Diabetes.”

After the war, in 1787, members of his hometown of Glastonbury voted to give Simbo land on Chestnut Hill Road on which he could build a house. The last surviving reference to Simbo is the record of his death on December 14, 1810.

This hollow-cut of Prince Simbo offers a rare glimpse of the likeness of an African American patriot. This profile, similar in construction to a silhouette, was likely cut at the end of the 18th century or the beginning of the 19th century. The quality of the image and frame is evidence of Simbo’s economic standing after the war.

After Independence, Life Following the Revolution

Rev. Lemuel Haynes Tray. Courtesy of the RISD Museum, Providence, RI.

Lemuel Haynes became a noted minister in Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Vermont. During the war he was a minuteman from Granville, Massachusetts and served at Fort Ticonderoga with Ethan Allen. Haynes wrote a poem about the Battle of Lexington and an anti-slavery essay, calling for the spirit of independence to apply to all men, regardless of color.

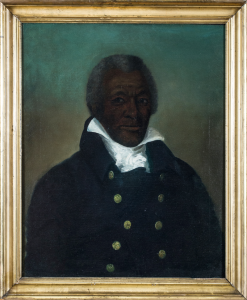

James Armistead Lafayette by John B. Martin. Courtesy of The Valentine, https://thevalentine.org.

James Armistead Lafayette served the Marquis de Lafayette during the American Revolution as a double agent. This portrait shows him as an older man, fashionably dressed in a blue coat with gold buttons decorated with eagles and likely painted around the time of the Marquis de Lafayette’s visit to the United States in 1824.

Agrippa Hull was a free Black man from Stockbridge, Massachusetts, who enlisted in the Continental Army in 1777 as a private in the Massachusetts Line. He was an orderly, first to General John Paterson and then to Polish nobleman General Thaddeus Kosciusko, General Washington’s chief engineer. Hull’s service included fighting in battles as far flung as Saratoga in New York and Eutaw Springs in South Carolina.

After the war, Hull returned to Stockbridge, buying a half-acre plot of land and establishing a farm which he expanded over the years. By the early 1800s he was a successful yeoman farmer, the largest Black landowner in the town, and his assets were more than 40 percent of the white inhabitants. In his old age he was a respected community elder, sharing stories of his war experiences and dispensing folk wisdom saying, “It is not the cover of the book, but what the book contains is the question. Many a good book has dark covers.” He died May 21, 1848, Stockbridge’s last surviving Revolutionary War veteran.

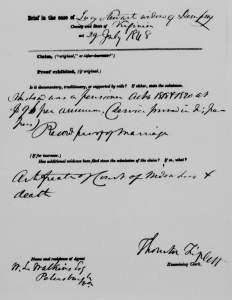

Emancipation document for Austin Dabney. Courtesy of the Georgia State Archives, Georgia Archives, RG 37-1-15, ah00006.

Austin Dabney was an enslaved man from Georgia who joined the Georgia militia as a substitute for Richard Aycock, his enslaver. He served in the artillery under Lieutenant Colonel Elijah Clark. In 1786, in recognition of his service, the state of Georgia paid Aycock for Dabney’s emancipation and granted him two hundred and fifty acres of land as a bounty for his services, he is the only Black veteran of the American Revolution from Georgia to receive land from the state.

John Chavis pension request. Courtesy of the South Carolina Department of Archives

In 1780, John Chavis petitioned the South Carolina legislature for a pension, saying he was unable to support himself “by his Labour,” on account of “the many wounds he received in an engagement with some Tories . . . at a place called Ramsours.” His name marked with an “X” distinguishes him from another Black patriot, John Chavis of Virginia, who became a noted educator in North Carolina in the nineteenth century.

Legacy

The legacy of the American Revolution is as complex and filled with contradictions as the people who lived through it. The traditional narrative of the evil red coats and the heroic patriots fighting for freedom is far more nuanced when looking at the objects, stories, lives, and perspectives of the people who were actually there. The same people who yelled “we will not be slaves to England” held thousands of Black people in bondage and stole Native lands. Many of the leaders of the Revolution fighting for their own freedom denied it to others. Yet some of the Native Americans and Black people who sided with the patriot cause saw hope in the words of the Revolution. Those words would allow for generations of people to chip away at the nation’s foundation of white supremacy. Each generation of Americans pushes the United States closer to the ideals of the Revolution.

Doctor Primus was a Revolutionary War soldier from Connecticut who, after the war became one of the first professionally trained Black doctors. He learned his profession as an apprentice to his enslaver, Dr. Alexander Wolcott of Windsor, Connecticut. Literate, he signed his name on his manumission documents “Dr. Primus Manumit.” Over the next three generations the Primus family attained middle class status and education, founding the Primus Institute in Talbot County, Maryland to educate newly free people following the American Civil War.

Photograph of Holdridge Primus, grandson of Dr. Primus. Courtesy of the Connecticut Historical Society, Photograph of Holdridge Primus, 1983.27.1.

Because of Nero Hawley’s patriotic service his great-grandsons, James and Augustus Hawley, filled out an application for membership in the Connecticut Society of Sons of the American Revolution. Nero Hawley received his freedom and became a successful brick-maker and entrepreneur, lived, died, and was buried in Trumbull, Connecticut.

Treasury note, State of Connecticut, June 1, 1782. Courtesy of Hugh B. Price, Hugh B. Price, President and CEO of the National Urban League: 1994–2003, Great-great-great-great grandson of Nero Hawley.

This cancelled treasury note is the pay certificate for Nero Hawley. The amount written on the note, partially obscured by the punched hole, was for one-fourth of the amount. The back of the note includes inscriptions indicating interest paid to him yearly, as well as Hawley’s mark.

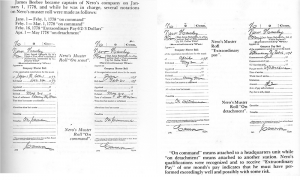

Ancestor’s Service Record for Nero Hawley. Courtesy of Hugh B. Price, Hugh B. Price, President and CEO of the National Urban League: 1994–2003, Great-great-great-great grandson of Nero Hawley.

When James and Augustus Hawley applied for membership in the Sons of the Revolution in the State of Connecticut, they filled out their ancestor’s service, detailing Nero Hawley’s military career.

Hugh Price remembers . . .

“After joining the National Urban League, my wife and I were invited to a reception in conjunction with an exhibit that featured old books, manuscripts, documents and other things of historical significance to African-American history. . .

There was a catalogue as a part of the exhibit that I bought and sent to my mother. After she received it, she called me and asked me if I knew what was in the exhibit? I told her I did not and she then told me there was a document that our ancestor, Nero Hawley, had actually signed in the late 1700s.

I contacted the curator of the exhibit and I was told a collector owned the document and it would not be possible to obtain it. I called back again because I really wanted it. The document means an incredible amount to my family and my mother’s search for Nero. It’s more than a collectible to us; I know it is a collectible for the collector, but for us it is different. I asked him to reconsider relinquishing ownership and he told me it was mine . . .

It was a Friday afternoon when the document arrived in my office at the former headquarters of the National Urban League on East 62nd Street in New York City. I opened up the pouch and there it was, a paper my ancestor had actually signed two hundred years ago. I can’t begin to describe how that felt. I was numb, just like a vegetable, the rest of the day. I did not call my mother right away to tell her I had it. My wife and I took it up to her on the Cape and presented it to her as a gift. It was the culmination of her journey of discovery to connect the family dots all the way back to Nero Hawley.

It was one of the special moments in my life. And to think of the fact that it happened because of the chance acceptance of an invitation to go stargazing followed by the eagle eye of my mother, the archivist.”

Hugh Price’s mother, Charlotte Price, is the great-great- granddaughter of Nero Hawley.

Dempsey Stewart was a free Black man who enlisted in the 1st North Carolina Regiment for a period of eighteen months. After the war, he lived in Greensville County, Virginia where he married Lucy Berry. They settled in Brunswick County, Virginia, where they purchased at least 144 acres of land. At the time of his death in 1848, his two daughters were living in Indiana. He left his Brunswick County farm to John Stewart, who was to care for Dempsey’s widow Lucy.

In this letter written in 1819, William Hill, Secretary of State of North Carolina, certifies Dempsey Stewart’s service in the North Carolina Continental line.

Widow’s Pension Certificate. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration