Remembrance of Noble Actions

Artifacts

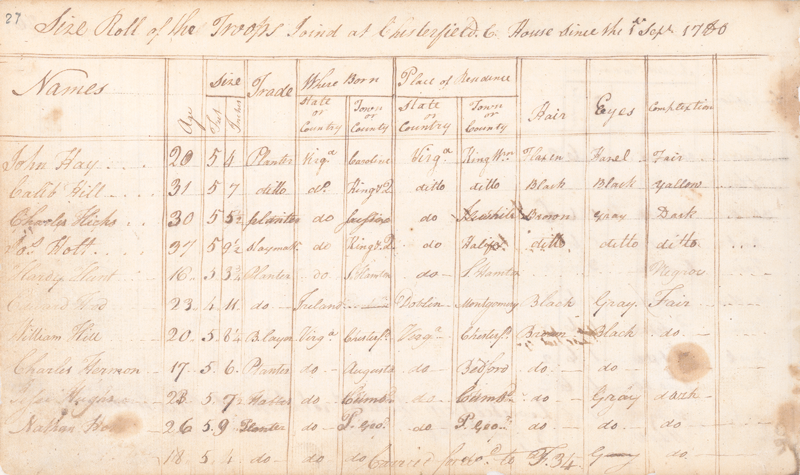

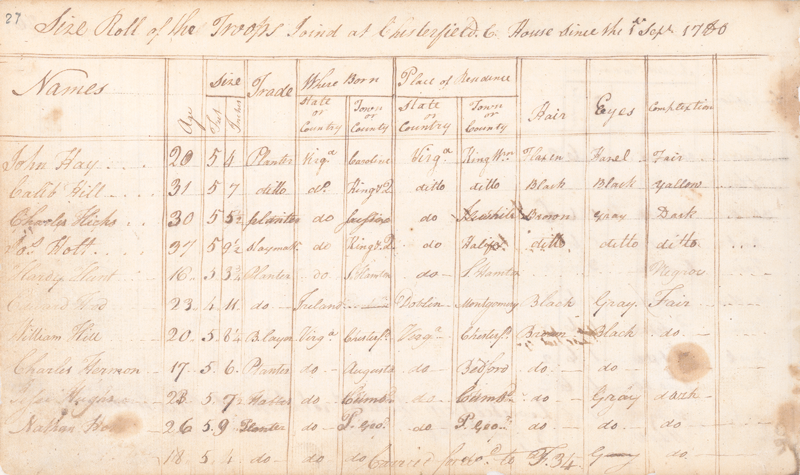

Page from "Chesterfield supplement".

Learn More

Page from "Chesterfield supplement".

Page from “Chesterfield supplement”. Courtesy of the Library of Virginia

Though most official military records make scant reference to physical appearance of soldiers, there are a few documents that do. Size rolls, while primarily meant to list soldiers’ heights, sometimes include descriptions of hair, eyes, and skin color. Among the more remarkable of these is the so-called “Chesterfield supplement,” delineating the physical attributes as well as the birthplaces of the enlistees.

John Scesux Engraved Powder Horn, 1750-1785.

Learn More

John Scesux Engraved Powder Horn, 1750-1785.

John Scesux Engraved Powder Horn, 1750-1785. DAR Museum Collection

Some Native Americans had no other choice than to side with the colonists. Although they were pacifists, John Scesux and other members of the Christian Brotherton community of Rhode Island were forced to prove their loyalty to the colonists or risk death and further displacement. The Brotherton community was comprised of displaced Native Americans of Algonquian roots who converted to Christianity from the New England area. Scesux mustered into Captain John Babcock’s Company in the Rhode Island Regiment of Battalion in March of 1778, to serve one year. After serving as a patriot in the American Revolution, John Scesux served the Brotherton Community as a trustee. He died in 1807 after the community relocated to New York. Eventually, the entire community was forced to relocate again to Wisconsin.

Portrait of Guy Johnson and Karonghyontye

Learn More

Portrait of Guy Johnson and Karonghyontye

Portrait of Guy Johnson and Karonghyontye, Benjamin West. Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington.

This portrait of Guy Johnson, British Superintendent of Indian Affairs of the Northern Department, and Karonghyontye (also known as David Hill) was painted in England in 1776. Johnson’s nephew Sir William Johnson, who had served in the same position and in 1759, married Molly Brant, sister of Joseph Brant, an influential Mohawk leader. Brant used his influence to persuade the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois Confederacy) to fight for the British. This ultimately came in 1777, when Clan Mothers accepted British promises to maintain supply lines to the nations. Formal nation-level agreements aside, Native towns were often divided in their loyalties, nearly half of Oneidas sided with the British, Tuscaroras and some Onondagas and Mohawks supported the Americans.

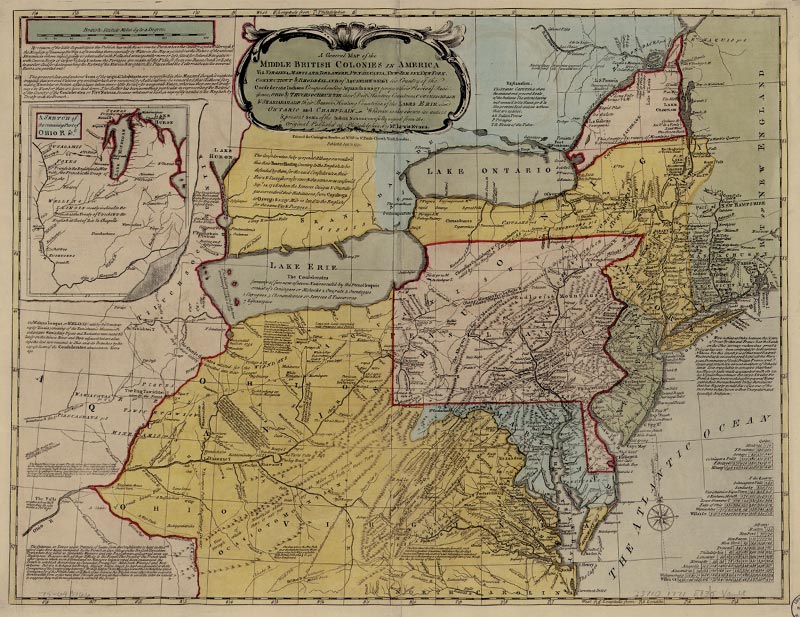

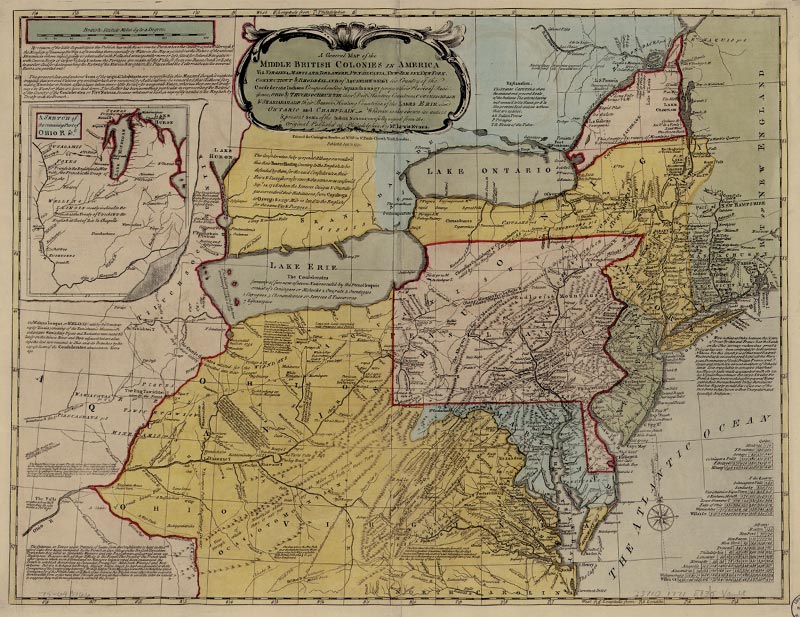

A General Map of the Middle British Colonies in America

Learn More

A General Map of the Middle British Colonies in America

A General Map of the Middle British Colonies in America, Lewis Evans, printed in 1771 for by Carington Bowles. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

This map of eight of the British colonies shows the locations of some of the Native nations living in the area.

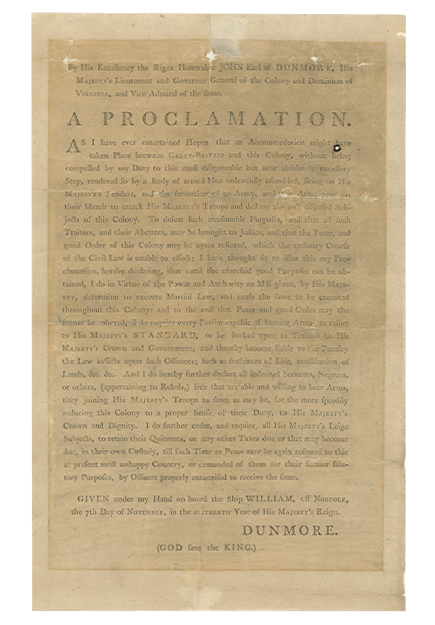

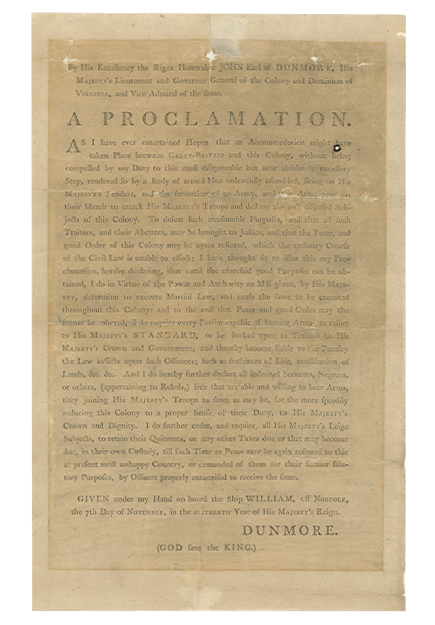

Reproduction of Dunmore's proclamation

Learn More

Reproduction of Dunmore's proclamation

Reproduction of Dunmore’s proclamation. Courtesy of the Library of Virginia.

In November 1775, Virginia’s royal governor Lord Dunmore offered freedom to enslaved men who would join him in fighting the colonists. Dunmore’s Proclamation declared martial law and invited those enslaved by the rebellious Americans (not those of loyalists) to join him: “And I do hereby further declare all indented [sic] Servants, Negroes, or others, (appertaining to Rebels,) free that are able and willing to bear Arms, they joining His MAJESTY’S Troops as soon as may be.” Word quickly spread, and, although estimates of the total numbers differ, at least 400 enslaved men joined Dunmore’s troops. Some of these men formed Dunmore’s “Ethiopian Regiment,” outfitted with uniforms emblazoned with the motto “Liberty to Slaves.”

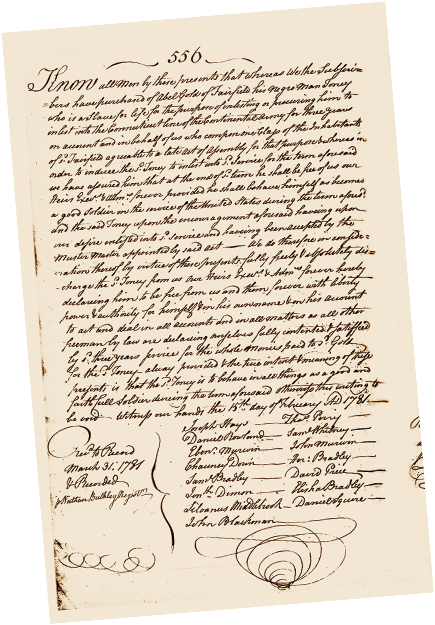

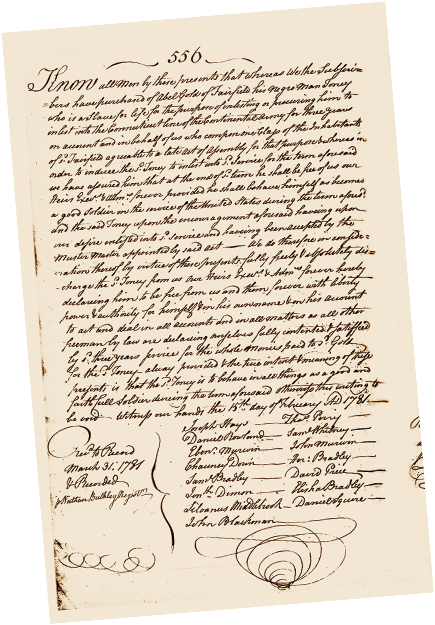

Document describing Connecticut slave Toney as a substitute

Learn More

Document describing Connecticut slave Toney as a substitute

Document describing Connecticut slave Toney as a substitute. Courtesy of Fairfield Archives, Fairfield, CT.

In this document, fifteen citizens of Fairfield, Connecticut, attest that they purchased an enslaved man named Toney from Abel Gold, for the purpose of having him serve in the Continental Army. For this service, they promised him his freedom. Having been accepted by the Muster Master, Toney is now free “from us, our Heirs, . . . forever” — that is providing that Toney remains a “good and faithfull soldier.” Otherwise, “this writing be void.” Toney’s choice to remain in the army was not his own; the document required him to serve for a minimum of three years or be forced back into slavery.

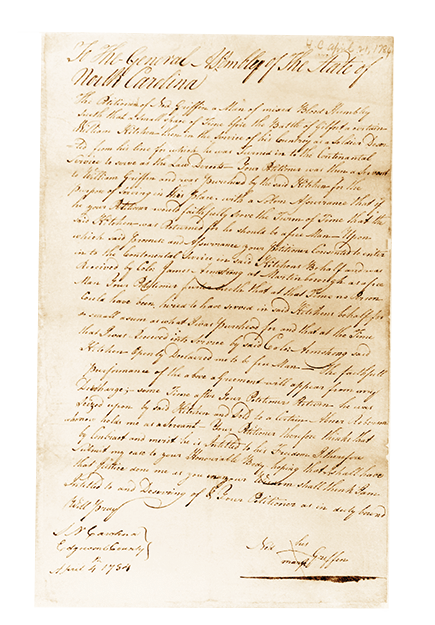

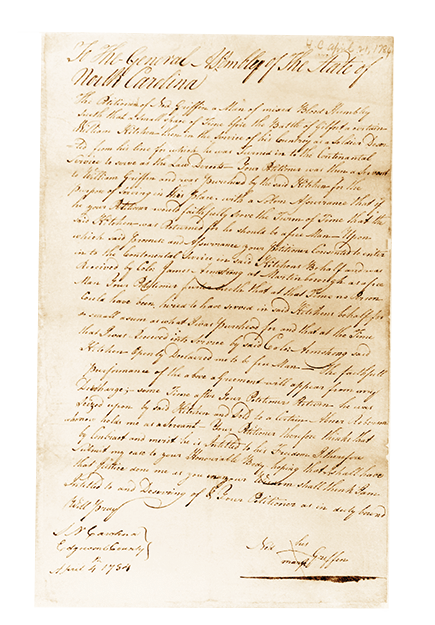

Ned Griffin's Petition to the General Assembly of North Carolina, April 21, 1784

Learn More

Ned Griffin's Petition to the General Assembly of North Carolina, April 21, 1784

Ned Griffin’s Petition to the General Assembly of North Carolina, April 21, 1784. Courtesy of the State Archives of North Carolina Office.

In North Carolina, Edwin (Ned) Griffin, served in place of his owner, William Kitchen, in exchange for his freedom. Kitchen purchased Griffin from his previous enslaver for the sole purpose of using him as a substitute in the Continental Army. At war’s end, Griffin was not emancipated and had to sue for his freedom. In this document, Ned Griffin outlines the circumstances of his enlistment, and states that, contrary to the agreement made in 1781, at war’s end his owner William Kitchen sold him to “a certain Abner Roberson.” Griffin appeals to the legislature, “hoping that I shall have that Justice done me as you in your Wisdom shall think I am Intitled to.” The General Assembly freed Ned Griffin later that year, by an Act of Emancipation.

George Washington by John Trumbull

Learn More

George Washington by John Trumbull

George Washington by John Trumbull. Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Charles Allen Munn, 1924

In 1780, artist John Trumbull painted George Washington accompanied by an enslaved, liveried servant wearing a turban. Historians believe this young man is William Lee, the General’s valet.

The Washington Family, Edward Savage

Learn More

The Washington Family, Edward Savage

The Washington Family, Edward Savage. Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington.

Other enslaved people accompanied their owners, often doing the same work for them that they did at home. Among the most famous of these enslaved men was William Lee, George Washington’s personal servant. Lee lived out his life at Mt.Vernon, and was buried in the slave cemetery there.

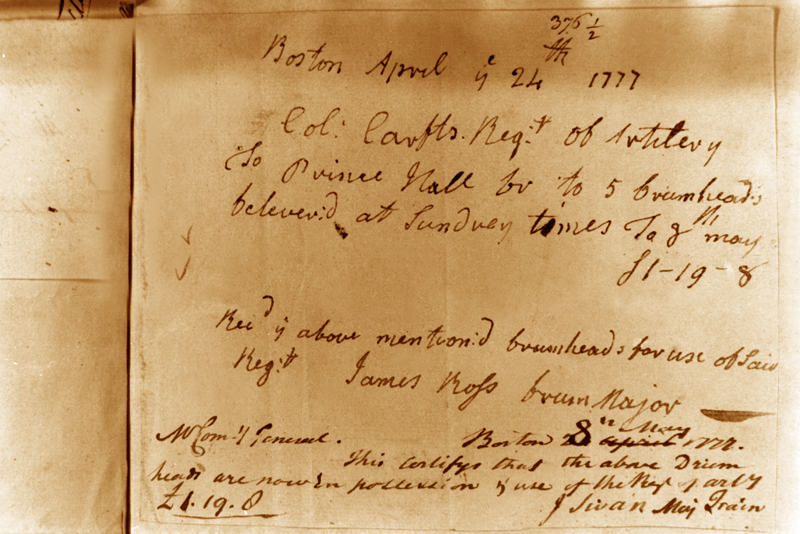

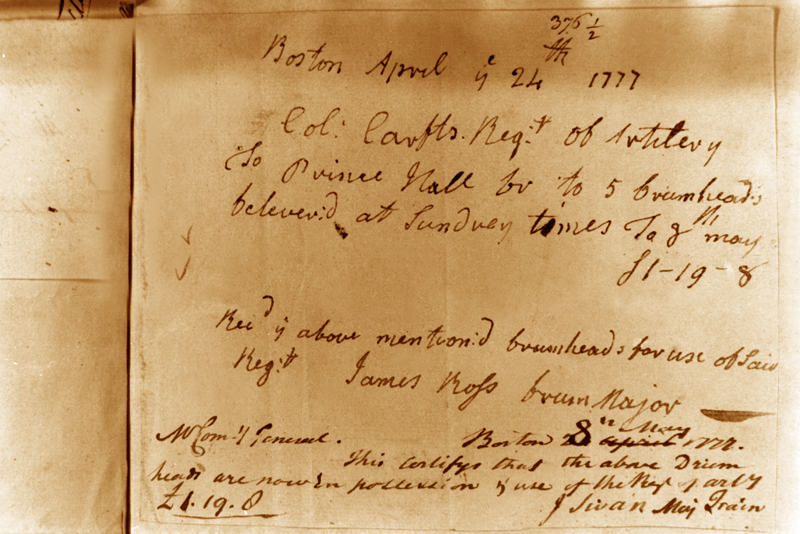

Bill of Sale for drumheads, Prince Hall

Learn More

Bill of Sale for drumheads, Prince Hall

Bill of Sale for drumheads, Prince Hall. Courtesy of the Massachusetts State Archives

Prince Hall was a formerly enslaved man who worked as a leather dresser. In 1777, he billed Col. Thomas Crafts’ regiment of artillery for drumheads he supplied. James Ross, drum major of that regiment, signed the invoice.

Page from Virginia Auditor of Public Accounts Entry 218, Revolutionary War Service Page, List of Officers who Received Certificates.

Learn More

Page from Virginia Auditor of Public Accounts Entry 218, Revolutionary War Service Page, List of Officers who Received Certificates.

Page from Virginia Auditor of Public Accounts Entry 218, Revolutionary War Service Page, List of Officers who Received Certificates.” Courtesy of The Library of Virginia

This page from the Virginia State Auditor’s accounts shows that a Colonel Newton received a certificate for William Flora’s service during the Revolution, presumably to be given to Flora. When hostilities began, William Flora joined a local militia and fought valiantly at the Battle of Great Bridge outside Norfolk on Dec. 9, 1775. Later he joined the 15th Virginia Regiment and served to the war’s end.

"A List of the Names of the Provincials who were Killed and Wounded"

Learn More

"A List of the Names of the Provincials who were Killed and Wounded"

“A List of the Names of the Provincials who were Killed and Wounded”. Courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society.

From the beginning of the Revolutionary War, men of color fought for the American cause. This undated broadside lists the names of those killed and wounded at Lexington and Concord, April 19, 1775. Among the wounded is “Prince Easterbrooks (A Negro Man).” Easterbrook went on to serve eight years in the militia and Continental Army. Upon dissolution of the Continental Army, Easterbrook returned to Lexington.

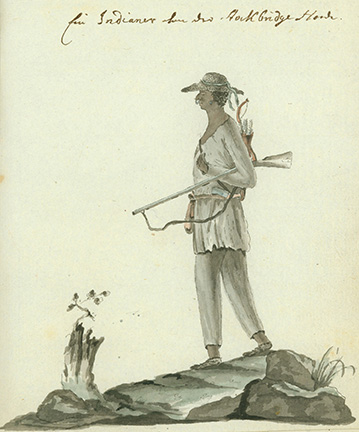

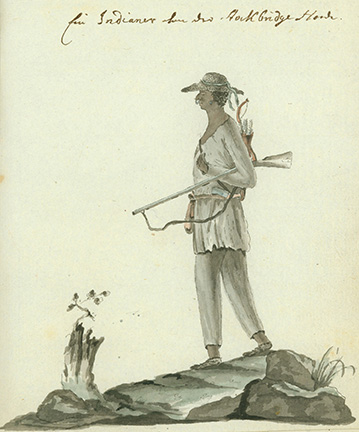

Mohican Indian in Stockbridge militia at White Plains, NY, watercolor sketch, 1778 from Johann von Ewald Diary.

Learn More

Mohican Indian in Stockbridge militia at White Plains, NY, watercolor sketch, 1778 from Johann von Ewald Diary.

Mohican Indian in Stockbridge militia at White Plains, NY, watercolor sketch, 1778 from Johann von Ewald Diary. Reproduction Courtesy Bloomsburg University, Andruss Library Special Collections, the Joseph Tustin Papers.

Hessian officer Johann von Ewald drew this sketch of a scout from Stockbridge, Massachusetts, serving in a militia unit under the command of Mohican Abraham Nimham, and encamped in 1778 at White Plains and the Bronx, New York. The sketch was done just before the skirmish with British Colonel John Simcoe’s Rangers during which as many as twenty Mohican patriots were killed, including Abraham Nimham and his father.

Lafayette at Yorktown by Jean-Baptiste Le Paon, 1783

Learn More

Lafayette at Yorktown by Jean-Baptiste Le Paon, 1783

Lafayette at Yorktown by Jean-Baptiste Le Paon, 1783. Courtesy of Lafayette College Art Collection, Gift of Helen Fahnstock Hubbard in Memory of her husband, John Hubbard.

The Black man in this portrait of the Marquis de Lafayette is believed to be James Armistead, who later took the last name Lafayette. He was an enslaved man from New Kent County, Virginia, who served Lafayette as a double agent in the camps of British Generals Benedict Arnold and Charles Cornwallis, near Portsmouth and Yorktown, Virginia.

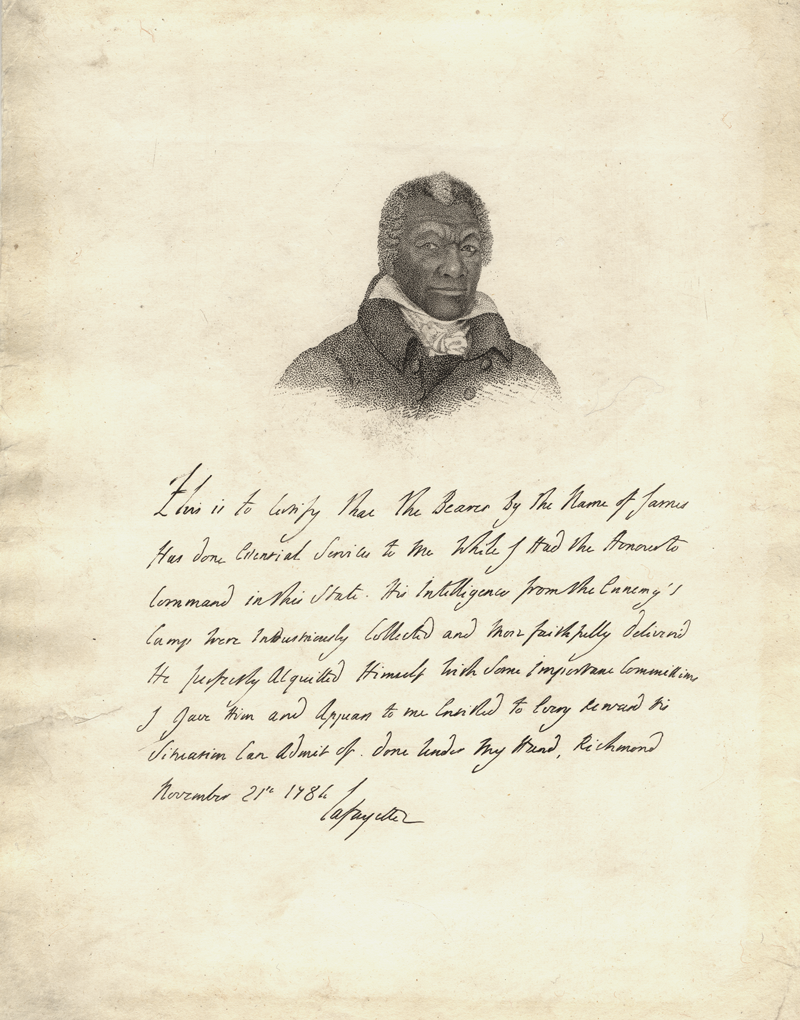

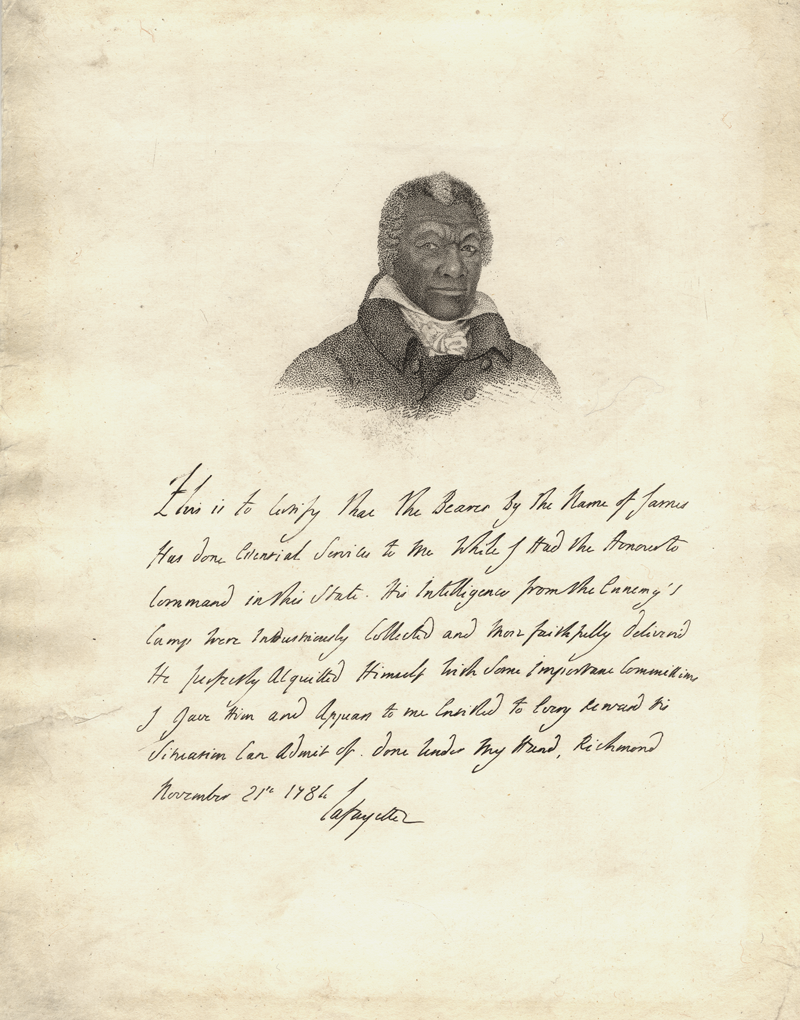

Certificate by Lafayette commending James Armistead Lafayette's service.

Learn More

Certificate by Lafayette commending James Armistead Lafayette's service.

Certificate by Lafayette commending James Armistead Lafayette’s service. Reproduction courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society

Before leaving America in 1784 the Marquis de Lafayette wrote a certificate for James (not yet known as Lafayette), commending him for his work as a spy. James had secured a position as Cornwallis’ servant and sent information to Lafayette concerning the British troop strength and plans.

The certificate reads:

“This is to certify that the bearer by the name of James has done essential services to me while I had the honour to command in this State. His intelligences from the enemy’s camp were industriously collected and more faithfully delivered. He properly acquitted himself with some important communications I gave him and appears to be entitled to every reward his situation can admit of. Done under my hand, Richmond, November 21st, 1784. LaFayette”

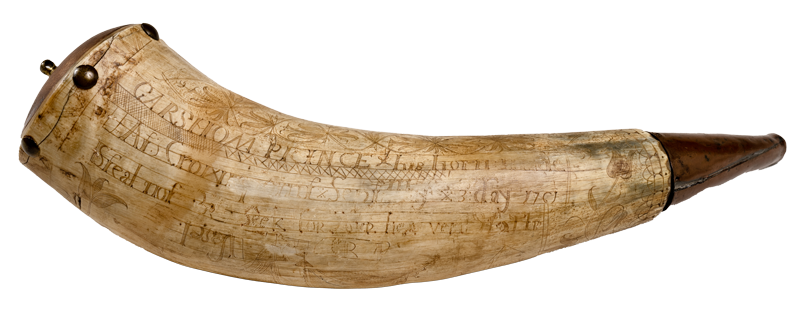

Powder horn carved by Garshom Prince, 1761

Learn More

Powder horn carved by Garshom Prince, 1761

Powder horn carved by Garshom Prince, 1761. Courtesy of the Courtesy of the Luzerne County Historical Society

It is unclear whether Garshom (or Gershom) Prince was enslaved by or a hired servant of Captain Robert Durkee. The inscriptions on his powder horn indicate that he fought during the French and Indian War as well as in the American Revolution. He was killed at the Battle of Wyoming in Pennsylvania in 1778, along with Durkee. He carved this powder horn during the French and Indian War and made inscriptions and engravings on it, including when, where, and for whom (himself) he made the horn.

Bucks of America regimental flag, silk, 1776-1780.

Learn More

Bucks of America regimental flag, silk, 1776-1780.

Bucks of America regimental flag, silk, 1776-1780. Courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society

The Bucks of America was an all-Black militia company from Massachusetts probably led by African American Colonel George Middleton. They do not appear in any official military records of the war and little is known of their service. The regiment received this flag from Governor John Hancock, at a ceremony in Boston near the end of the American Revolution. The flag has 13 stars for the colonies, a buck, and pine tree as symbols of their regiment.

Bucks of America Badge, medallion, 1776-1780.

Learn More

Bucks of America Badge, medallion, 1776-1780.

Bucks of America Badge, medallion, 1776-1780. Courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society

Bucks of America regiment members received and wore this badge inscribed with their initials (for example the “M.W.” on this one).

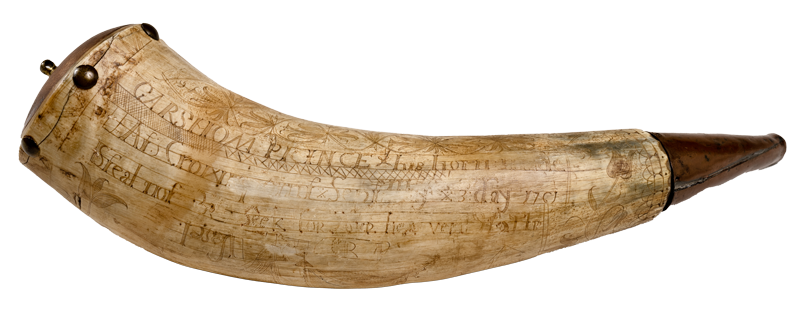

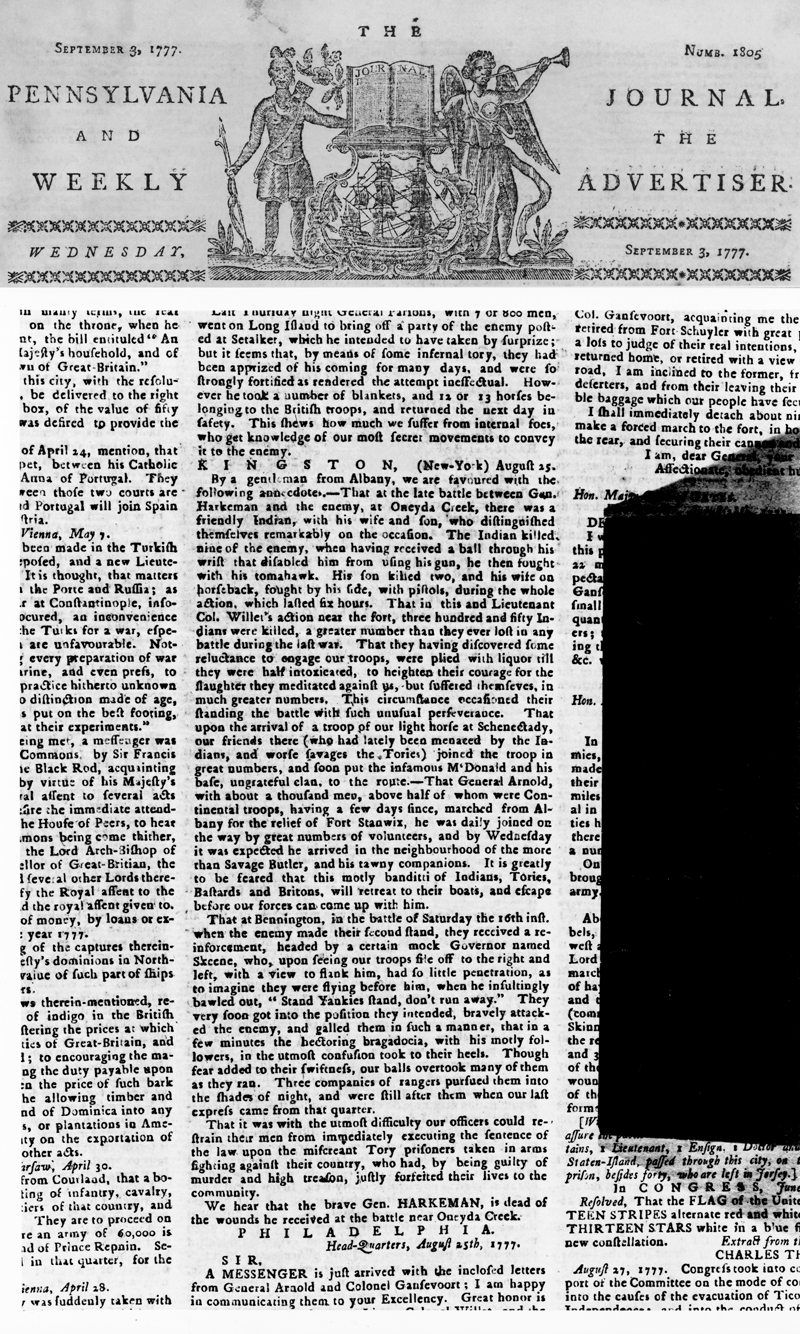

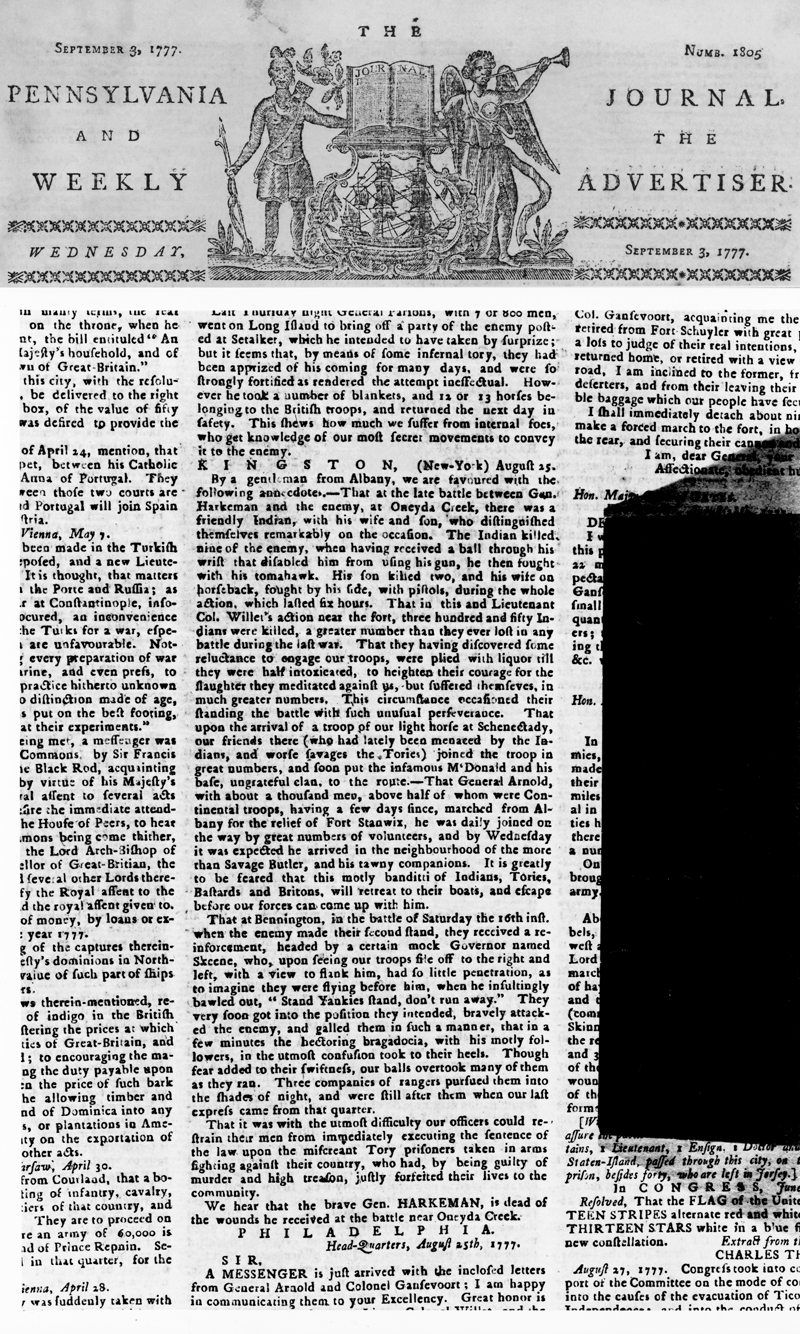

The Battle of Oriskany. Newspaper account from the Pennsylvania Journal and the Weekly Advertiser, September 3, 1777.

Learn More

The Battle of Oriskany. Newspaper account from the Pennsylvania Journal and the Weekly Advertiser, September 3, 1777.

The Battle of Oriskany. Newspaper account from the Pennsylvania Journal and the Weekly Advertiser, September 3, 1777. Courtesy of the Library Company of Philadelphia.

This account of the battle between “General Harkeman [sic] and the enemy at Oneyda Creek” describes the actions of a “friendly Indian” and his family who killed a large number of British soldiers. After the unnamed “Indian” was shot through the wrist, his wife, on horseback, fought by his side “with pistols.” Oneida oral tradition recounts that this unnamed Native American was Hanyere, Oneida leader and long-time foe of the British ally, Joseph Brant.

Although the Battle of Oriskany was not a clear-cut victory for either side, it forced the British General Barry St. Leger to retreat and prevented his troops from reaching Saratoga. In retaliation for the Oneida’s support of the Americans during the Battle of Oriskany, Mohawks allied with the British destroyed the Oneida village of Oriska.

John Neptune, portrait by Obadiah Dickenson

Learn More

John Neptune, portrait by Obadiah Dickenson

John Neptune, portrait by Obadiah Dickenson. Portrait of Penobscot Lieutenant Governor John Neptune (1836) Collections of the Maine State Museum (#79.40.283).

When his portrait was painted in 1836, John Neptune was a Lieutenant Governor of the Penobscots. During the American Revolution, he was one of many Penobscot men who fought for the Americans, helping defend Maine’s frontier from British incursions from Canada.

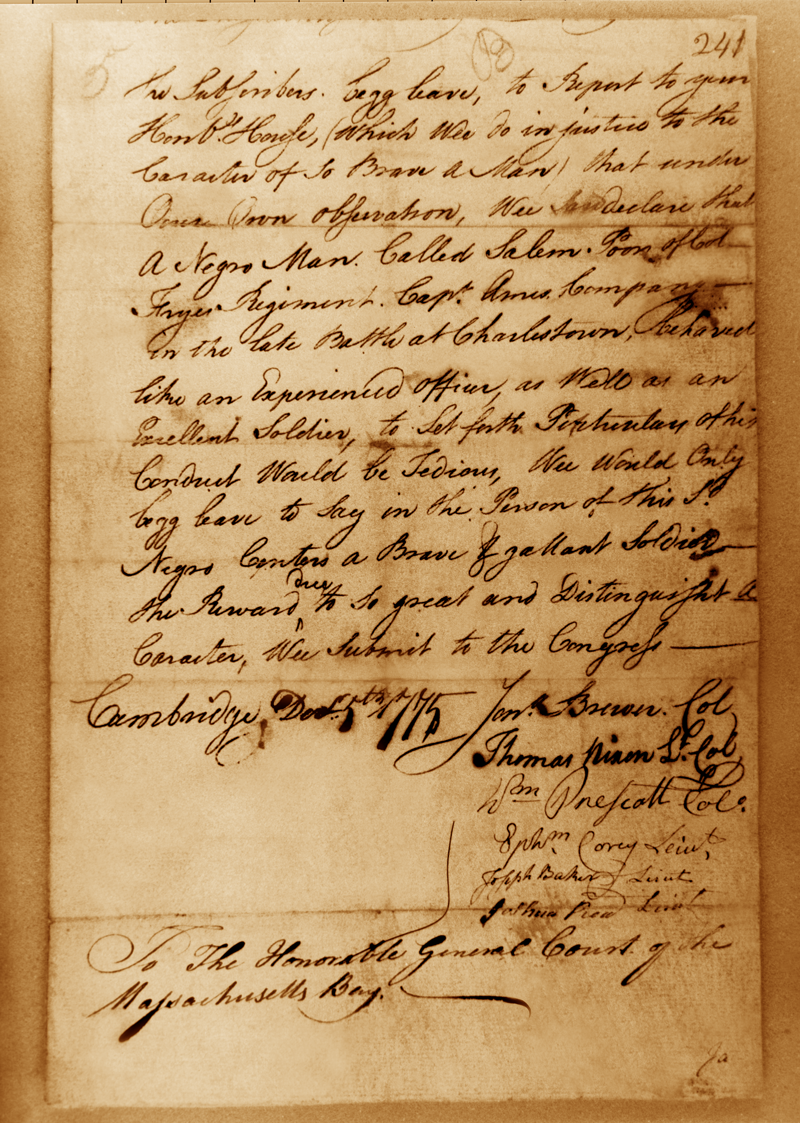

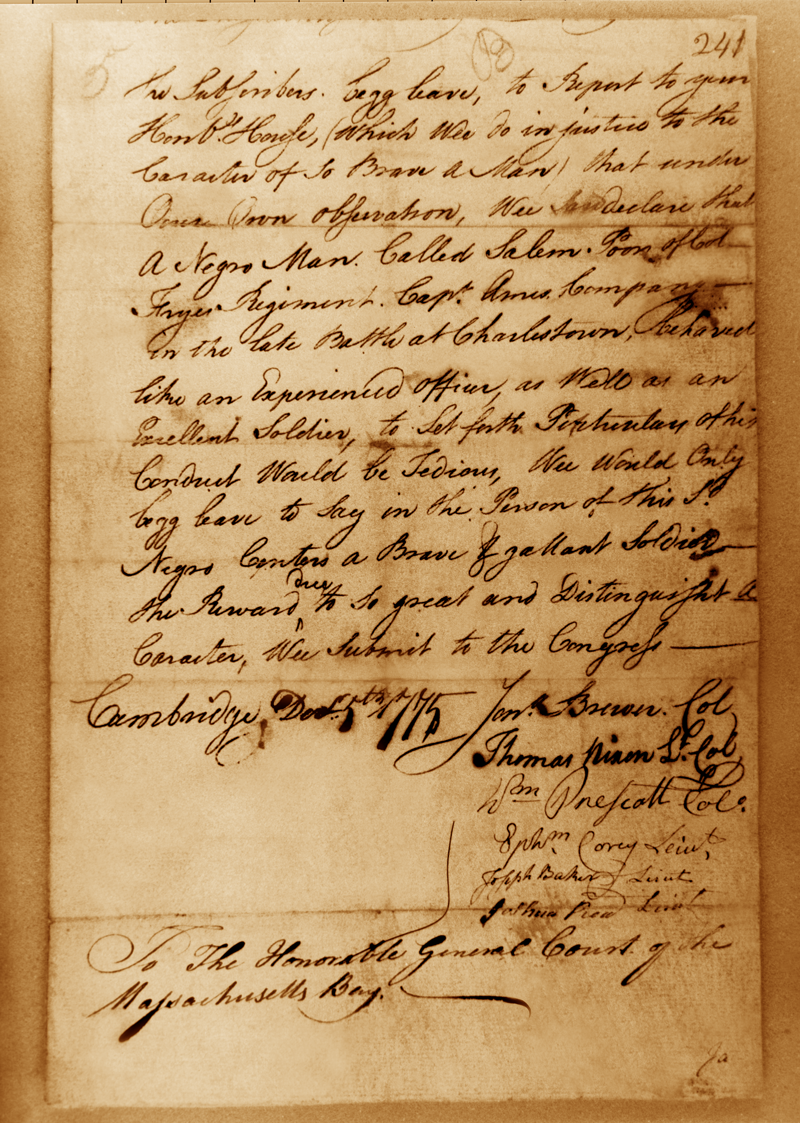

Recommendation of Salem Poor for bravery

Learn More

Recommendation of Salem Poor for bravery

Recommendation of Salem Poor for bravery. Courtesy of the Massachusetts State Archives

After Salem Poor’s service during the Battle of Bunker Hill where he reportedly killed British Lieutenant Colonel James Abercrombie, fourteen officers signed this document. Poor was a Black man from Massachusetts who also served at the Battle of White Plains and endured the crushing winter of 1777-78 at Valley Forge.

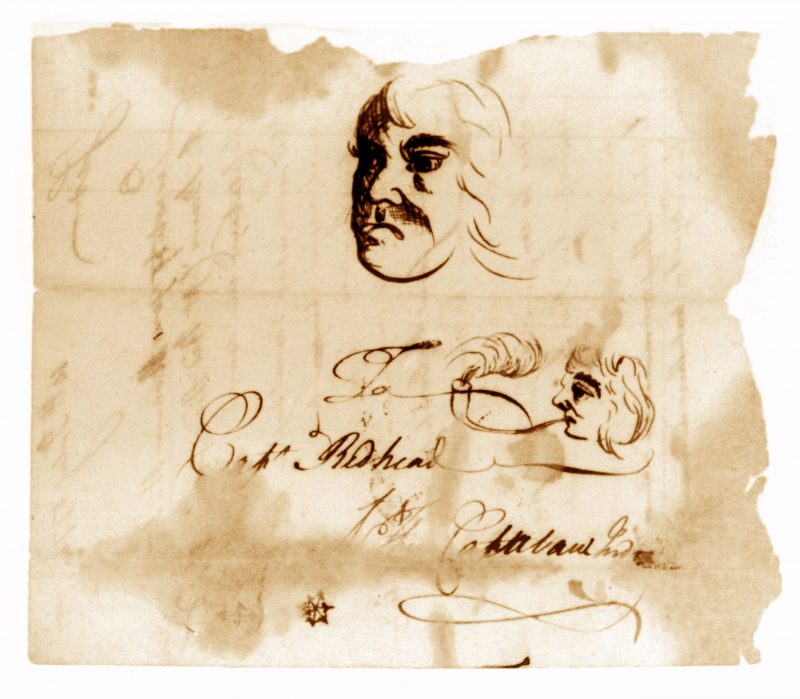

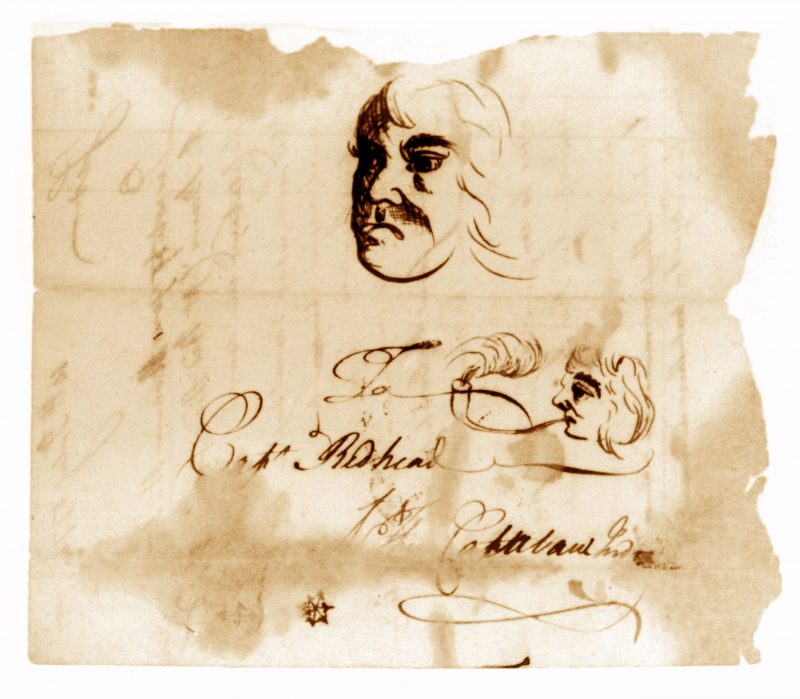

Drawing of Catawba Indian

Learn More

Drawing of Catawba Indian

Drawing of Catawba Indian. Courtesy of the South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC

The Catawba Nation of the Carolinas after having much of their land taken from them by white settlers, had come to depend on the colonial government for protection against their enemies, the Cherokee and the Haudenosaunee. Catawba warriors fought alongside the English during the French and Indian War. This drawing from the period of the American Revolution is of a Catawba warrior identified as “Captain Redhead.” There are at least two men named “Readhead” listed as American soldiers from the Catawba Nation.

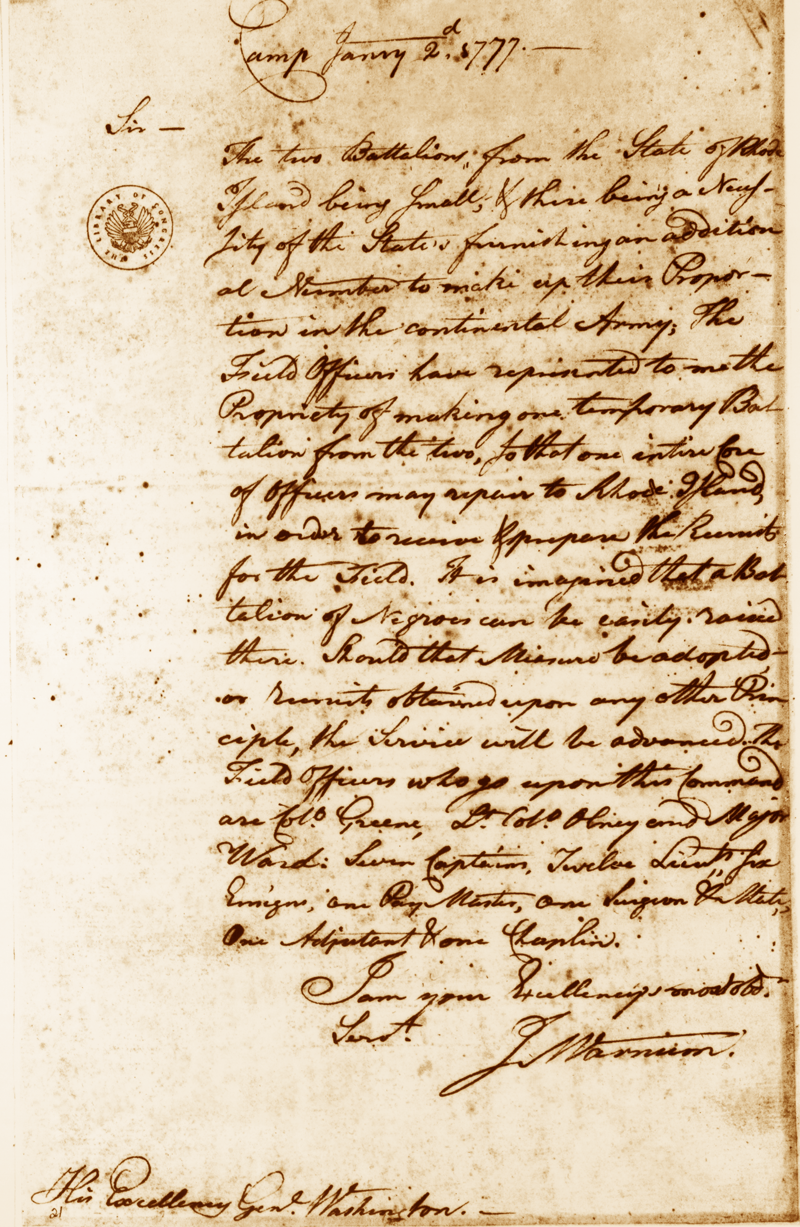

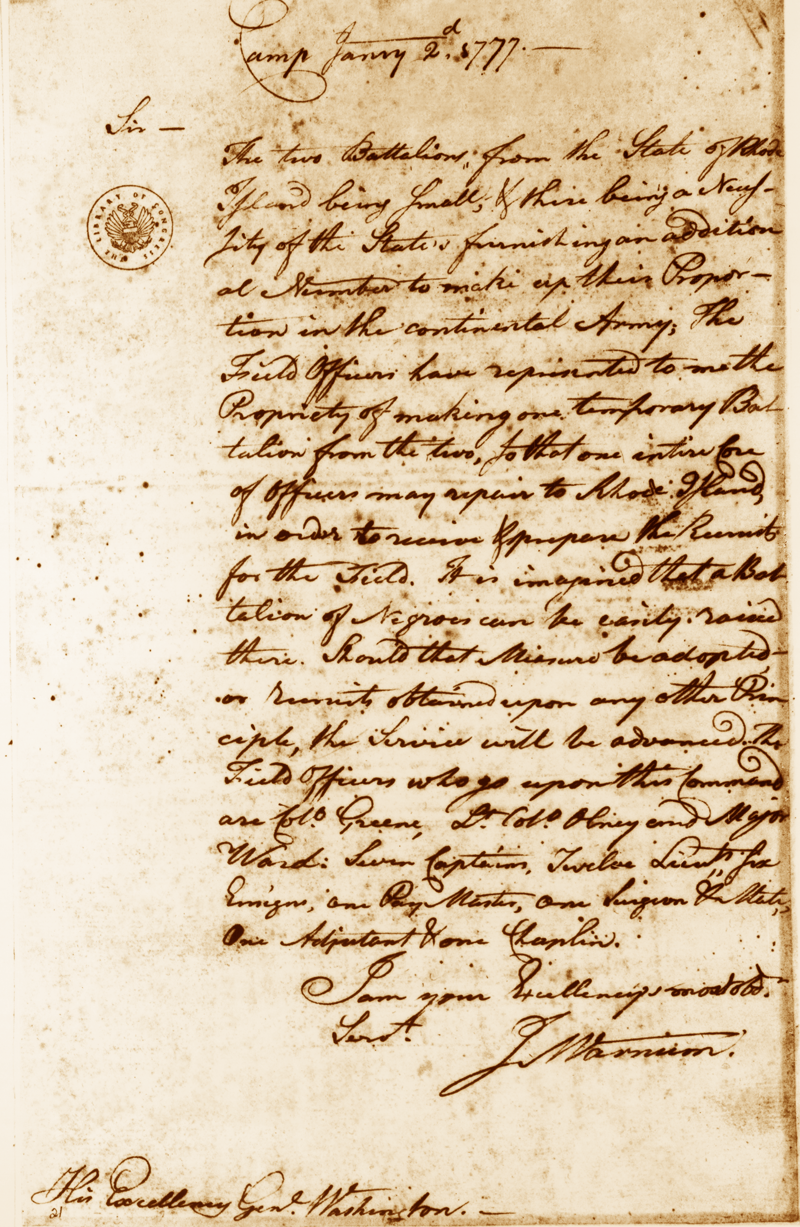

Letter from [J.] M. Varnum to George Washington, 2 January 1777.

Learn More

Letter from [J.] M. Varnum to George Washington, 2 January 1777.

Letter from [J.] M. Varnum to George Washington, 2 January 1777. Courtesy of the Library of Congress, George Washington papers

In his letter, General James Varnum, a Rhode Island lawyer prior to the war, proposed combining the two Rhode Island regiments and included a Black battalion. “It is imagined that a Battalion of Negroes can be easily raised there.” He named Colonel Christopher Greene and Lieutenant Colonel Jeremiah Olney as the “field officers” to command the unit.

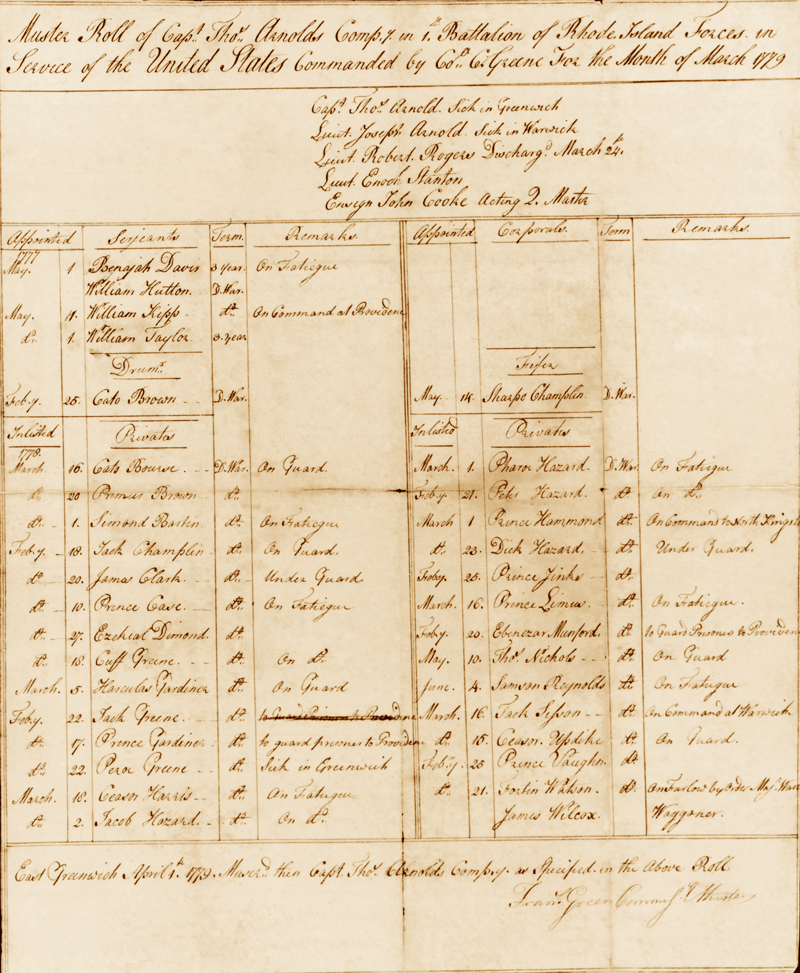

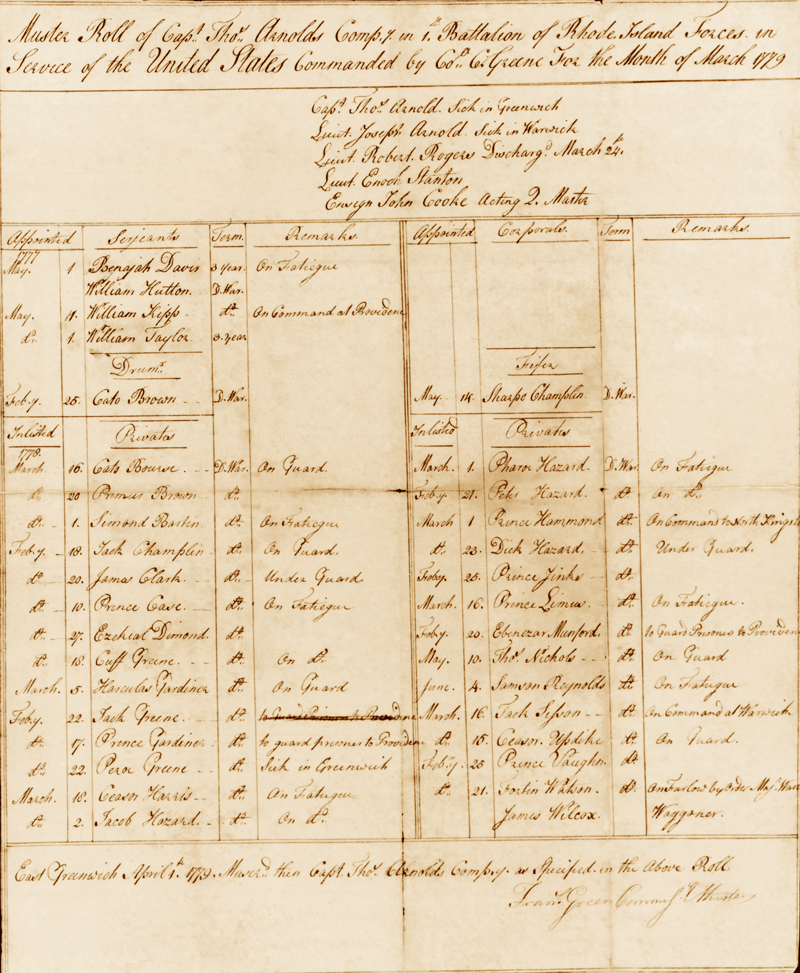

Muster Roll of Capt. Thomas Arnold Camp for 1st Battalion of Rhode Island Forces in Service of the United States Commanded by Col. Christopher Greene

Learn More

Muster Roll of Capt. Thomas Arnold Camp for 1st Battalion of Rhode Island Forces in Service of the United States Commanded by Col. Christopher Greene

Muster Roll of Capt. Thomas Arnold Camp for 1st Battalion of Rhode Island Forces in Service of the United States Commanded by Col. Christopher Greene. Courtesy of the Rhode Island Historical Society, Providence, Francis Green. Muster Roll of Captain Theodore Arnolds – Month of March 1779, East Greemwich, RI. April 1, 1779; ink on paper manuscript, MSS 673 B6 F29

This muster roll for the month of March 1779, lists the names of the members of an all-Black battalion.

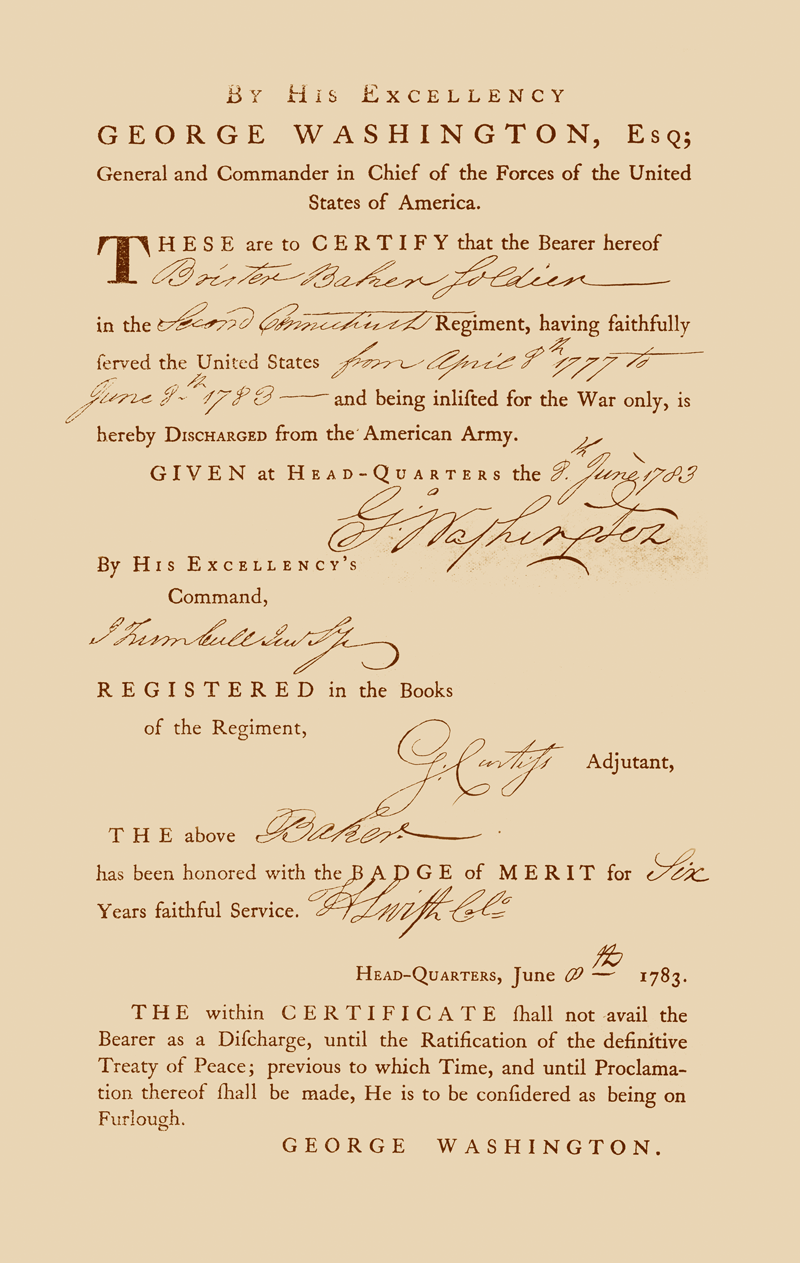

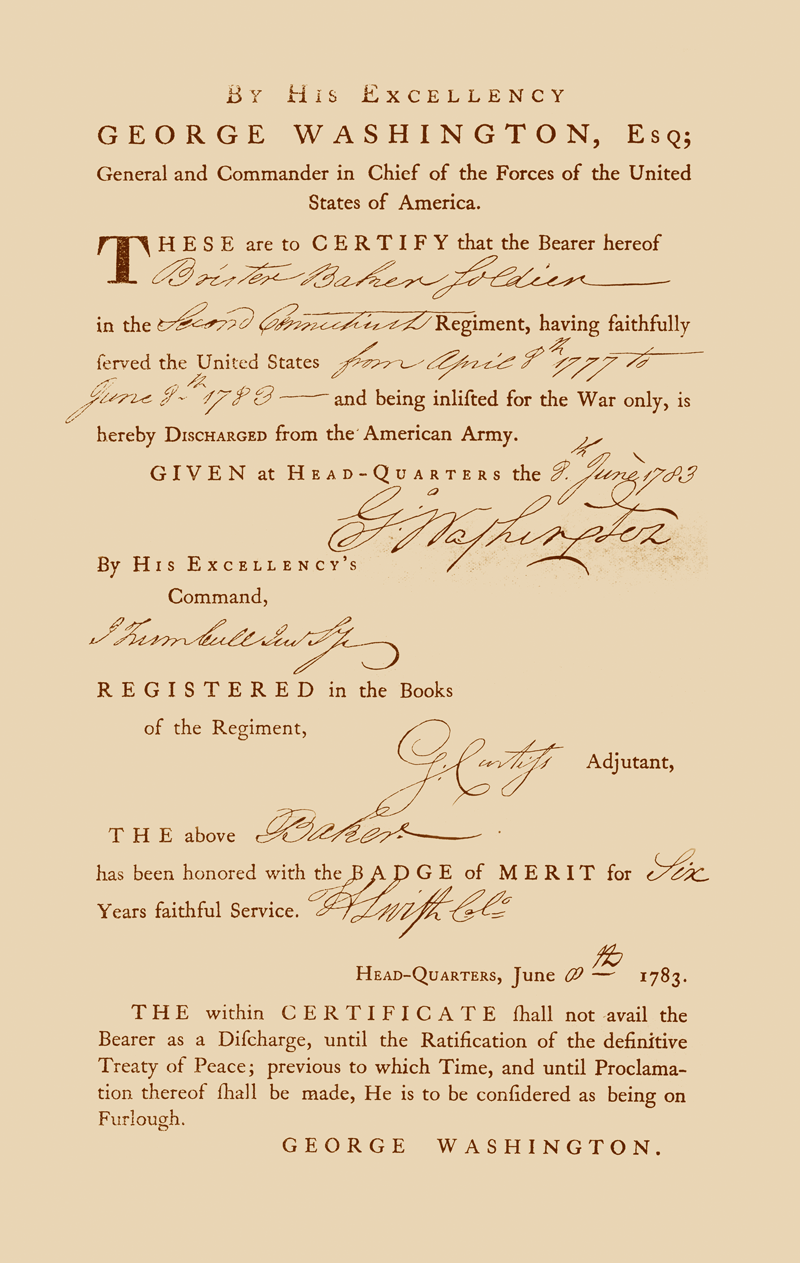

Discharge Certificate for Brister Baker

Learn More

Discharge Certificate for Brister Baker

Discharge Certificate for Brister Baker

Brister (or Bristol) Baker, a Black man, was a member of 2nd Connecticut Regiment during the American Revolution. George Washington signed his honorable discharge certificate. In 1855, William Cooper Nell reproduced the certificate in his book, Colored Patriots of the American Revolution.

Pewter plate

Learn More

Pewter plate

Pewter plate. Courtesy of Revolutionary Spaces.

This 18th-century pewter plate (one of a three-piece set) belonged to Jeffery Hartwell (Jesse Freeman), a Black soldier from Bedford, Massachusetts. He entered the local militia as the substitute for his enslaver, Joseph Hartwell. He later served in a number of Massachusetts regiments until discharged in 1779.

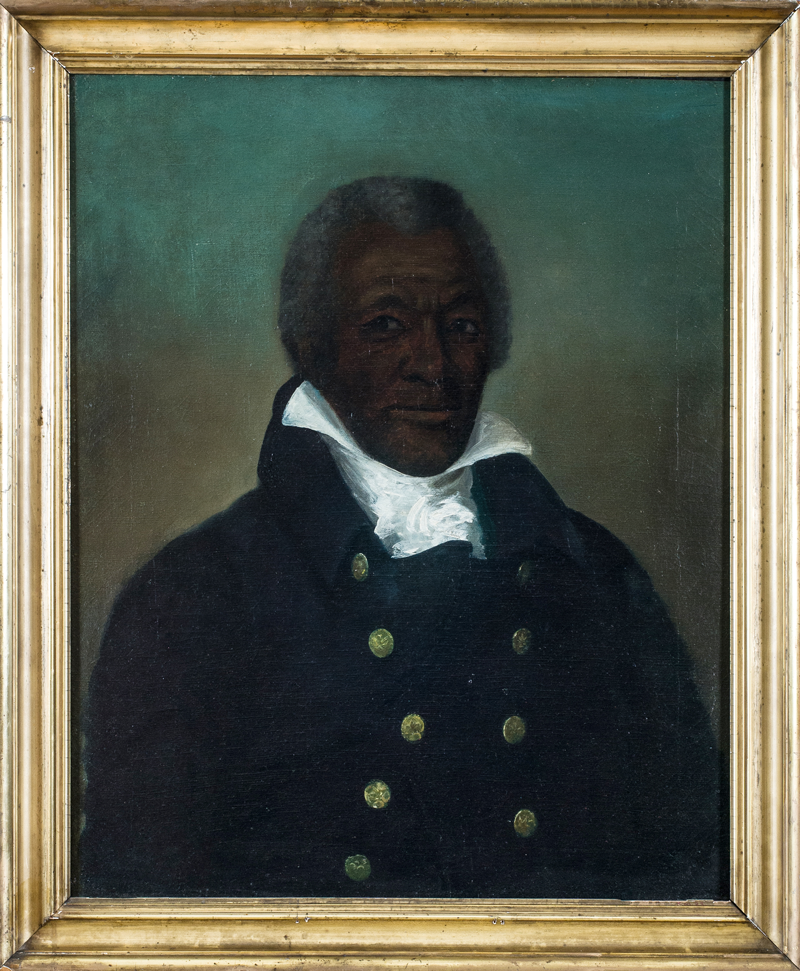

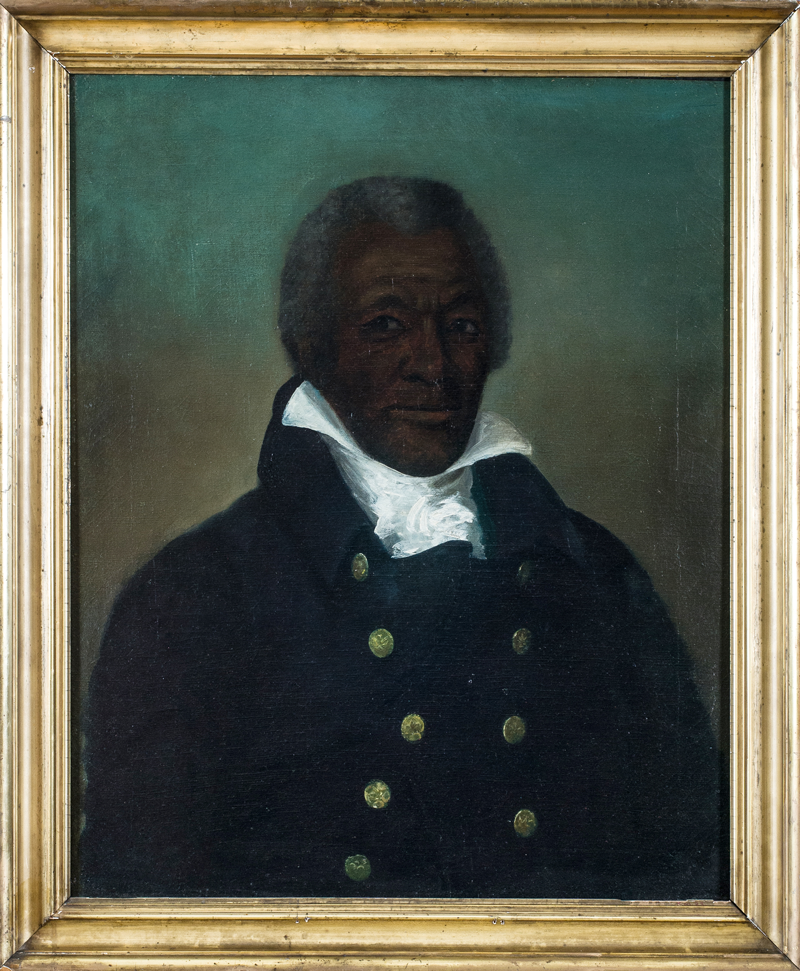

James Armistead Lafayette by John B. Martin

Learn More

James Armistead Lafayette by John B. Martin

James Armistead Lafayette by John B. Martin. Courtesy of The Valentine, https://thevalentine.org.

James Armistead Lafayette served the Marquis de Lafayette during the American Revolution as a double agent. This portrait shows him as an older man, fashionably dressed in a blue coat with gold buttons decorated with eagles and likely painted around the time of the Marquis de Lafayette’s visit to the United States in 1824.

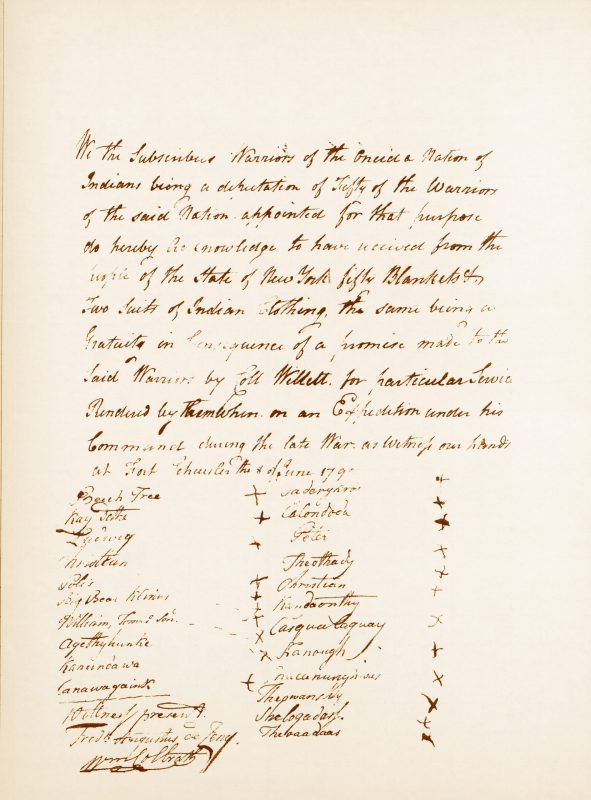

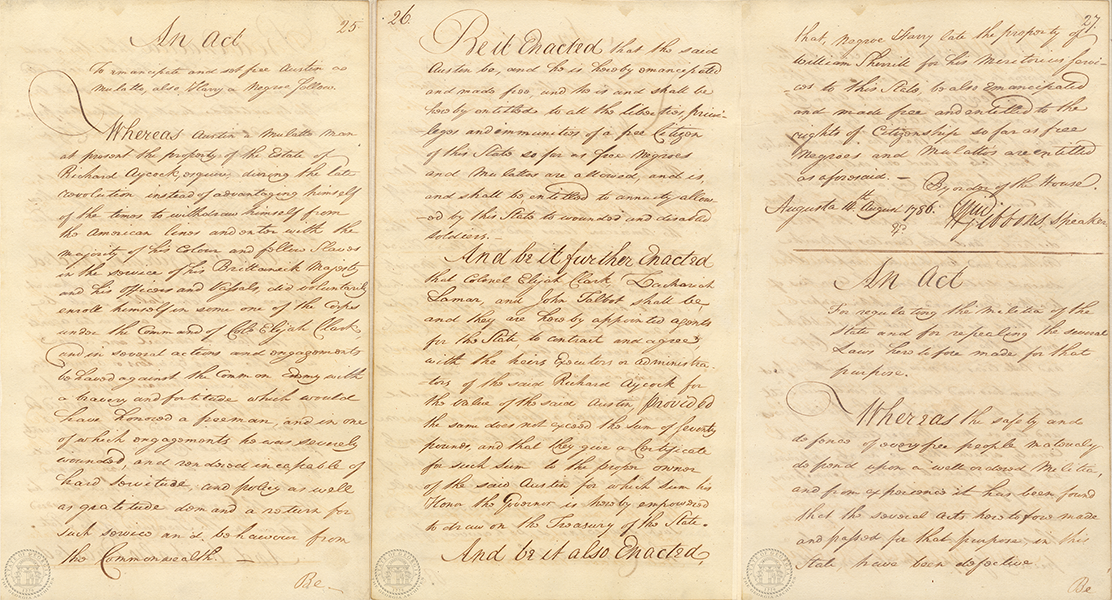

Receipt for blankets and clothing with list of Oneidas

Learn More

Receipt for blankets and clothing with list of Oneidas

Receipt for blankets and clothing with list of Oneidas. Courtesy of the New York State Archives. New York (State). Comptroller’s Office. Selected audited accounts of state civil and military officers, 1780-1858. Series A0802-78, Volume 15, p. 70b..

In 1792, a group of Oneidas received “fifty blankets and two suits of Indian clothing” as a gratuity for special services during the American Revolution. The names of twenty-two warriors are affixed to the document, along with their marks.

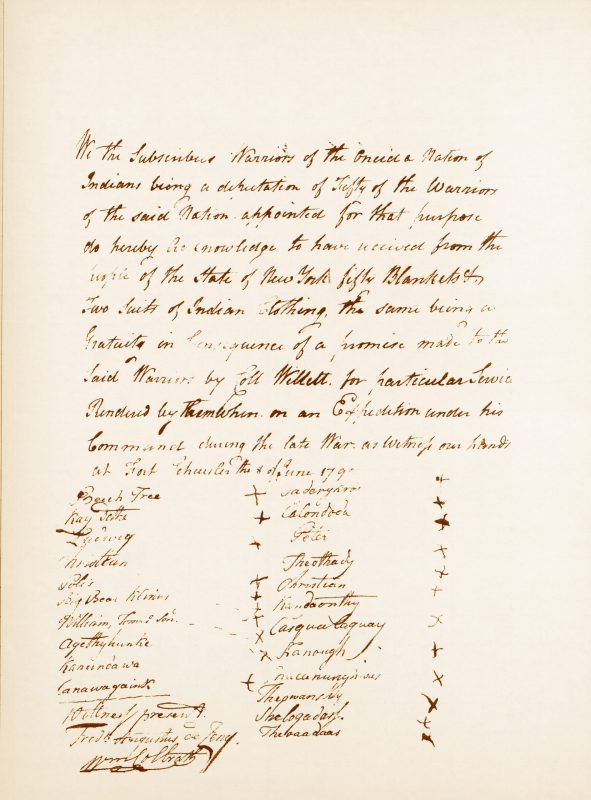

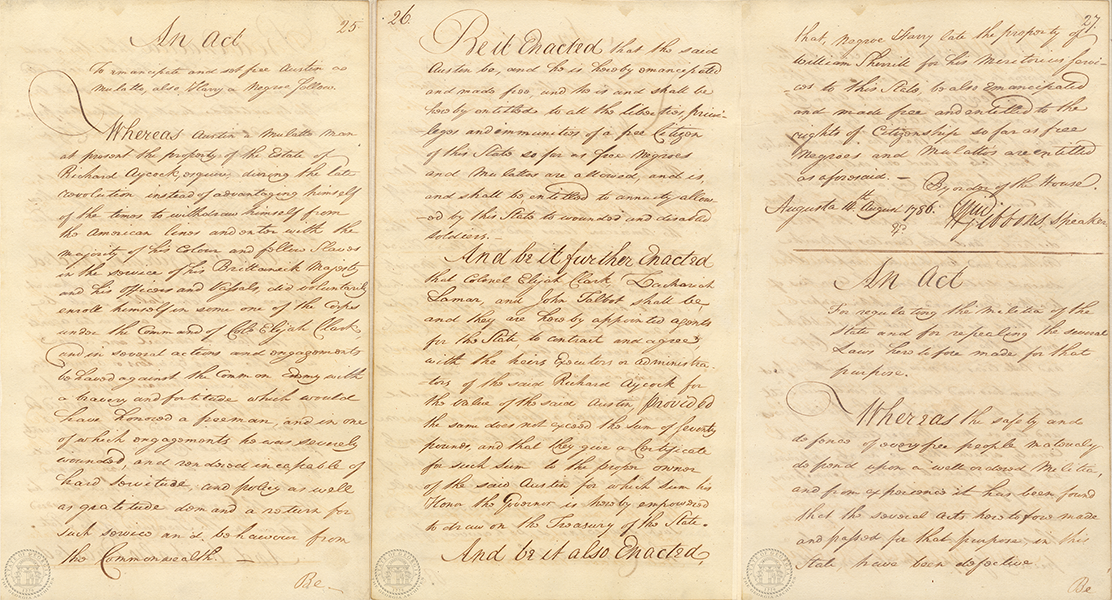

Emancipation document for Austin Dabney

Learn More

Emancipation document for Austin Dabney

Emancipation document for Austin Dabney. Courtesy of the Georgia State Archives, Georgia Archives, RG 37-1-15, ah00006.

Austin Dabney was an enslaved man from Georgia who joined the Georgia militia as a substitute for Richard Aycock, his enslaver. He served in the artillery under Lieutenant Colonel Elijah Clark. In 1786, in recognition of his service, the state of Georgia paid Aycock for Dabney’s emancipation and granted him two hundred and fifty acres of land as a bounty for his services, he is the only Black veteran of the American Revolution from Georgia to receive land from the state.

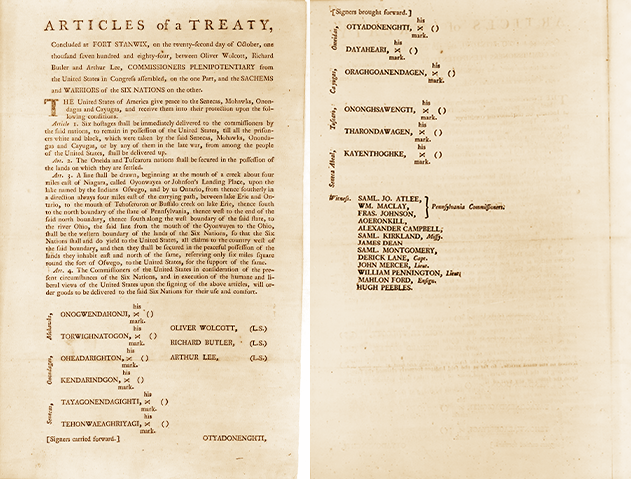

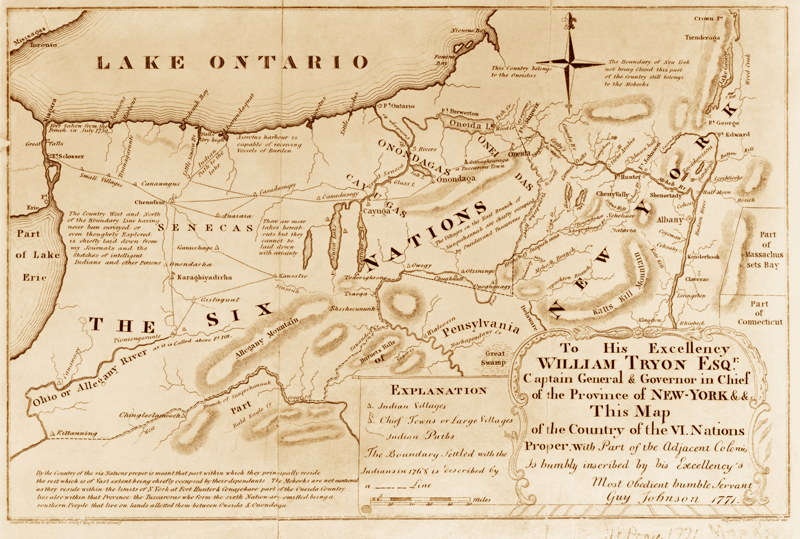

Treaty of Fort Stanwix, 1784. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Learn More

Treaty of Fort Stanwix, 1784. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Treaty of Fort Stanwix, 1784. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The Treaty of Paris of 1783 that ended the war with England made no provision for the Native American combatants. The Treaty of 1784 at Stanwix, between the United States and the Haudenosaunee, ended hostilities between the United States, its allies the Oneidas and Tuscaroras, and the four nations that sided with the British, the Mohawk, Seneca, Cayuga, and Onondaga. Representatives of all six nations signed the treaty.

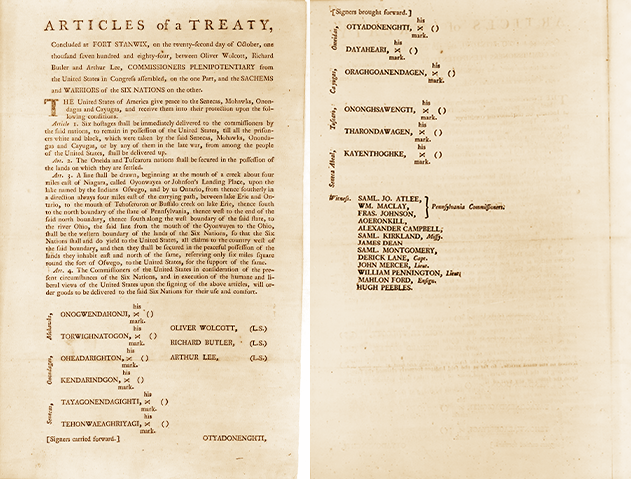

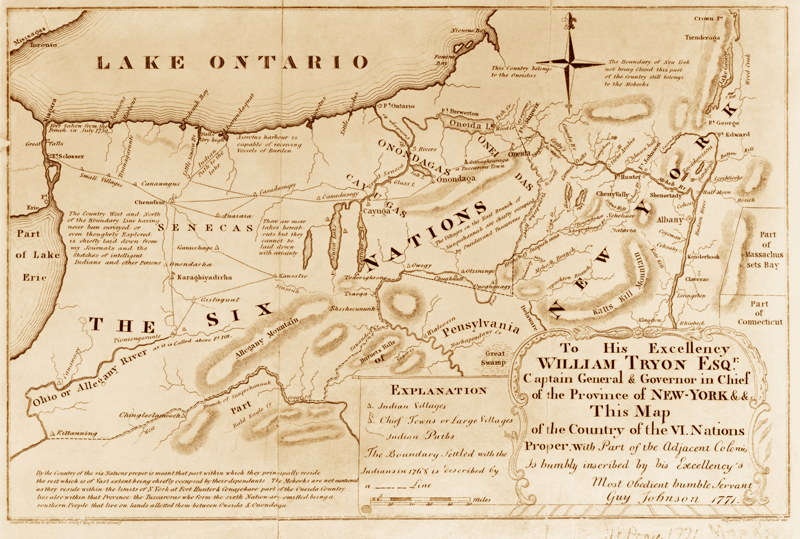

Guy Johnson's map of Indian lands

Learn More

Guy Johnson's map of Indian lands

Guy Johnson’s map of Indian lands. Courtesy of the New York Public Library

Guy Johnson drew this map for the British governor of New York, William Tryon. On it he located the Six Nations of the confederacy: the Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida, Mohawk, and Tuscarora. Most of these nations felt a deep loyalty to Sir William Johnson, who died in 1774, and subsequently to members of his family. They were also motivated by complicated and sometimes conflicting incentives, including land and economics. The Treaty of Fort Stanwix confirmed the possession of the lands of the Oneidas and Tuscaroras, and drew new boundaries for the other four nations, the Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga, and Oneida.

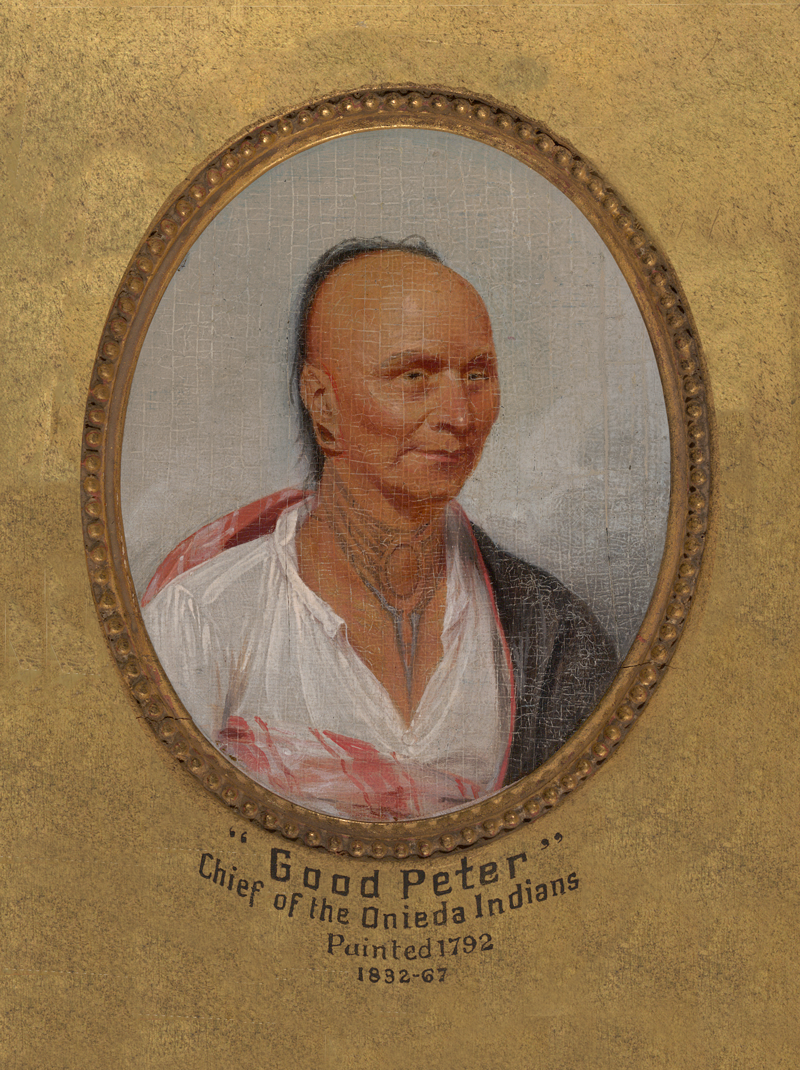

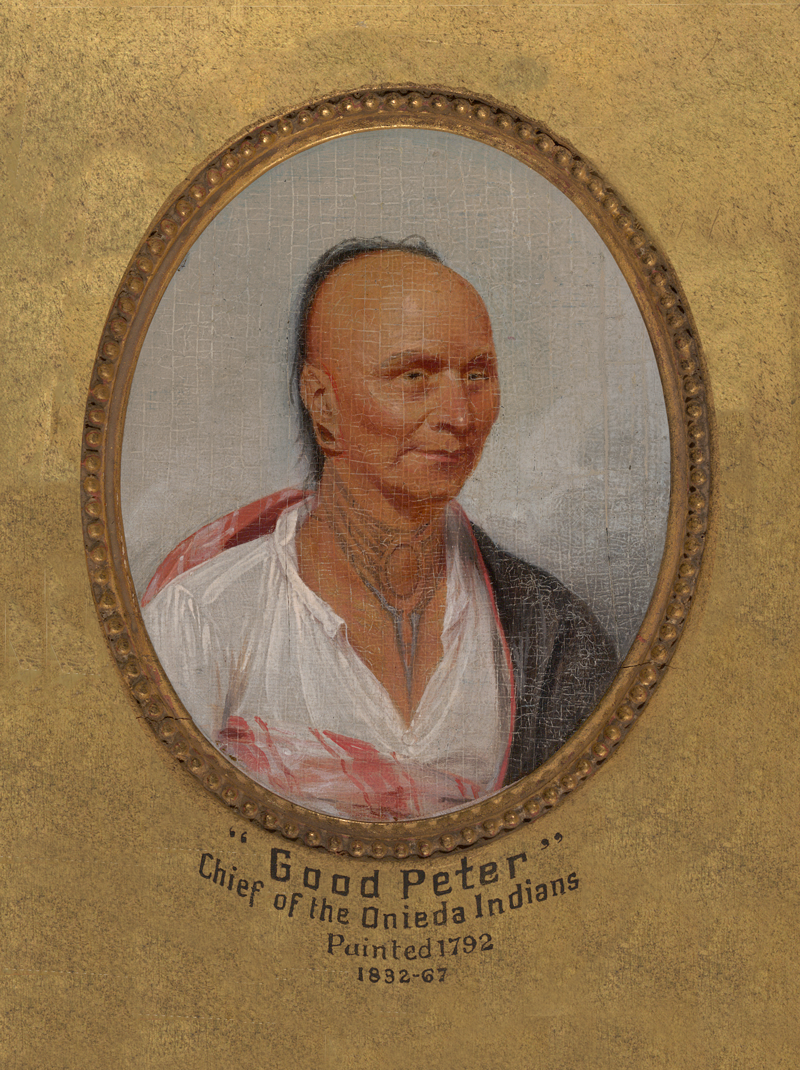

Portrait of Good Peter, John Trumbull, 1792

Learn More

Portrait of Good Peter, John Trumbull, 1792

Portrait of Good Peter, John Trumbull, 1792. Courtesy of Yale University Art Gallery, Trumbull Collection.

Oneida Chief Good Peter learned that New York Governor George Clinton and others were gradually taking the Oneida’s land in the name of saving it. Good Peter brought the case to the State of New York which conveniently decided that Clinton and others had purchased the land thereby dispossessing the Oneidas.

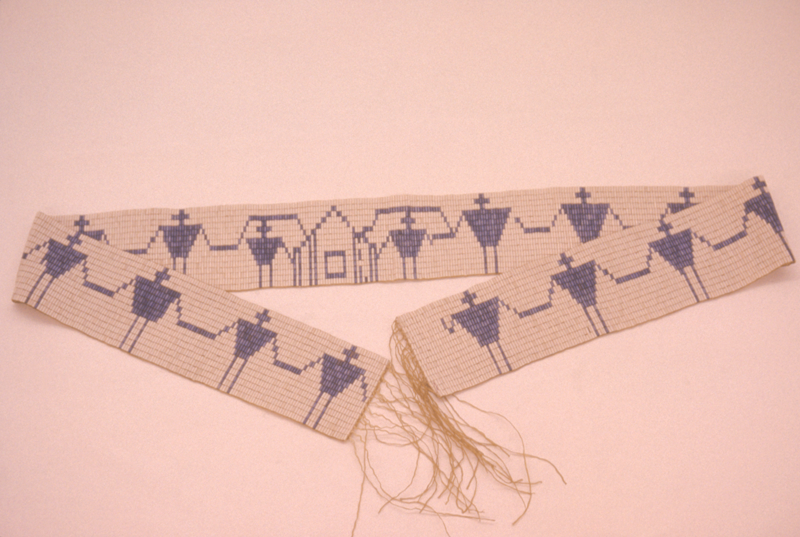

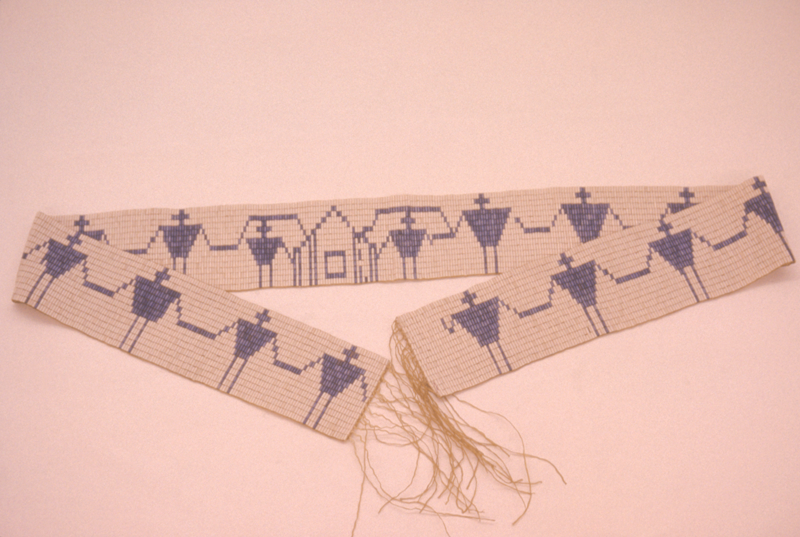

Reproduction wampum belt

Learn More

Reproduction wampum belt

Reproduction wampum belt. Photograph courtesy of the Carnegie Museum.

Belts of shell beads, called wampum, were used to seal contracts by both Native nations and colonial governments. The original belt, called the “George Washington Covenant Belt,” was commissioned by the new United States government and is believed to have sealed the Canandaigua Treaty of 1794. The original is in the custody of the Onondaga Nation.

Annuity Cloth

Learn More

Annuity Cloth

Annuity Cloth. Courtesy of the Oneida Indian Nation.

The Treaty of Canandaigua was signed November 11, 1794 between the United States and member nations of the Haudenosaunee (“Iroquois”) Confederacy. Over 200 years later, the treaty, like the U.S. Constitution, remains a living document. Though the agreement has been strained and terms of the treaty violated, its ideals are still upheld; the promise of friendship, peace, and lasting recognition of Native American sovereignty between the nations. There are commemorations in Canandaigua, New York, held each year by the Haudenosaunee people to mark the anniversary of the treaty. As a symbol of the tangible bond between the nations, the United States sends the Oneida, Seneca, Cayuga and Onondaga bundles of annuity cloth, like the ivory muslin here. Oneida Members for generations have accepted their pieces of “treaty cloth,” and it is still disbursed annually to the population of about 1,000 Oneidas in New York.

Elizabeth Freeman miniature portrait by Susan Anne Livingston Ridley Sedgwick, 1811

Learn More

Elizabeth Freeman miniature portrait by Susan Anne Livingston Ridley Sedgwick, 1811

Elizabeth Freeman miniature portrait by Susan Anne Livingston Ridley Sedgwick, 1811, Courtesy of the Collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society

Elizabeth Freeman in 1781 and Quock Walker in 1783, sued for their freedom arguing the principles of the American Revolution and the Massachusetts Constitution of 1780’s phrase that all men are “born free and equal.” These cases lead to the end of slavery in Massachusetts in 1783.

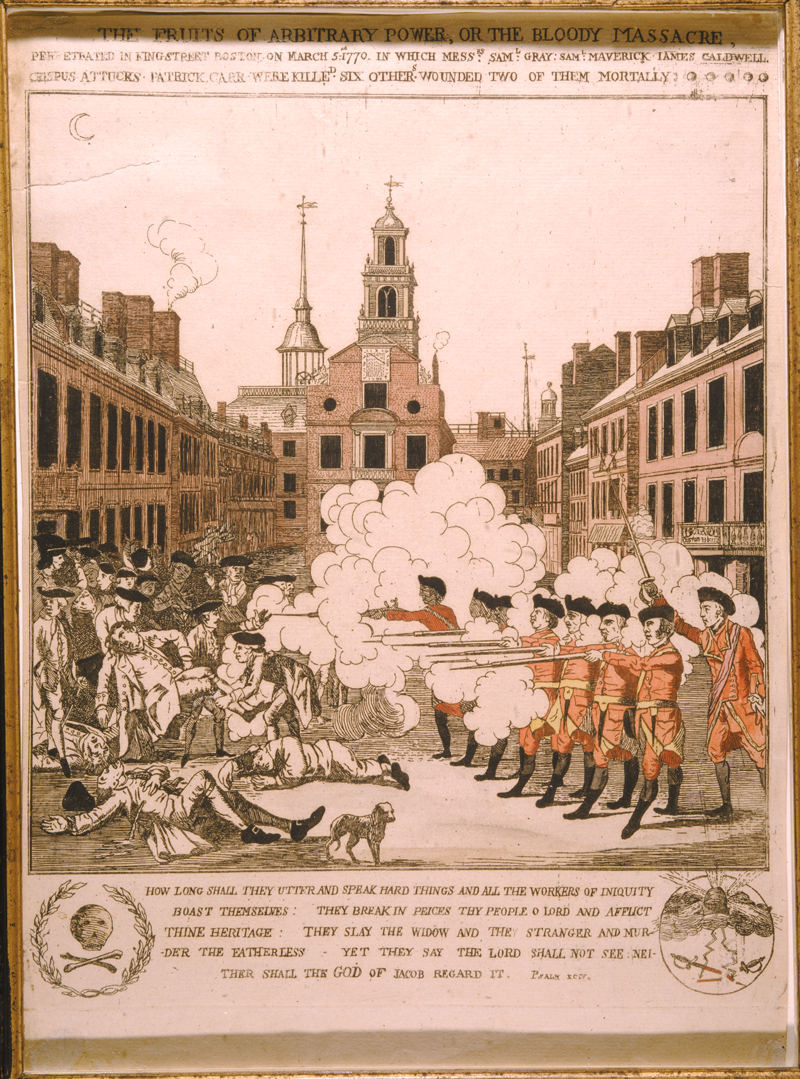

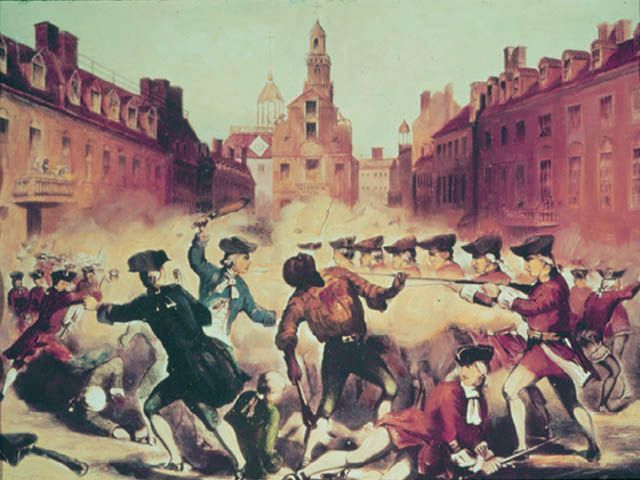

Reproduction of The Bloody Massacre, by Henry Pelham

Learn More

Reproduction of The Bloody Massacre, by Henry Pelham

Reproduction of The Bloody Massacre, by Henry Pelham. Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society

As the gun smoke cleared on March 5, 1770, five men lay dead, among them was Crispus Attucks. Images of the “Boston Massacre” were available for sale on the city’s streets almost immediately after the event took place. Paul Revere, silversmith and engraver, published his version of the “bloody massacre” after copying an engraving by Henry Pelham only twenty-one days after the event. Pelham’s engraving was published after Revere’s and is nearly identical. Neither shows a Black man among the dead and wounded. Attucks is described in contemporary accounts as mulatto. Crispus Attucks’ mother was Native American, a member of the Massachuset Nation, and his father is believed to be African.

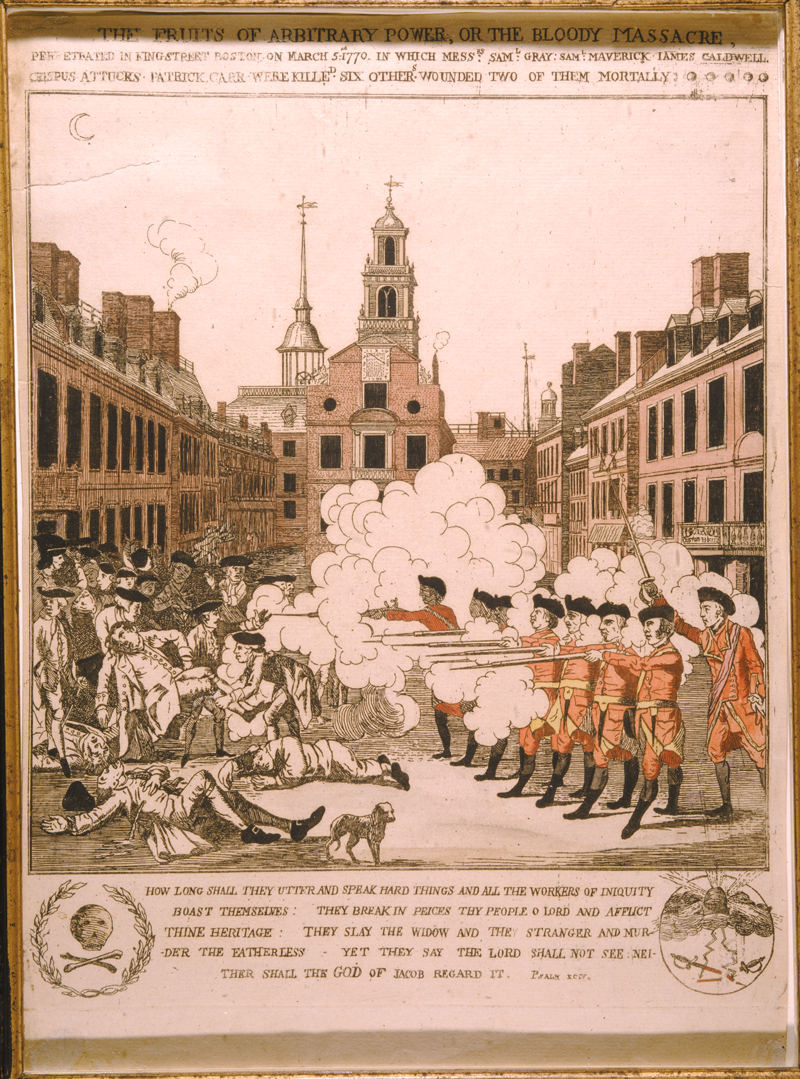

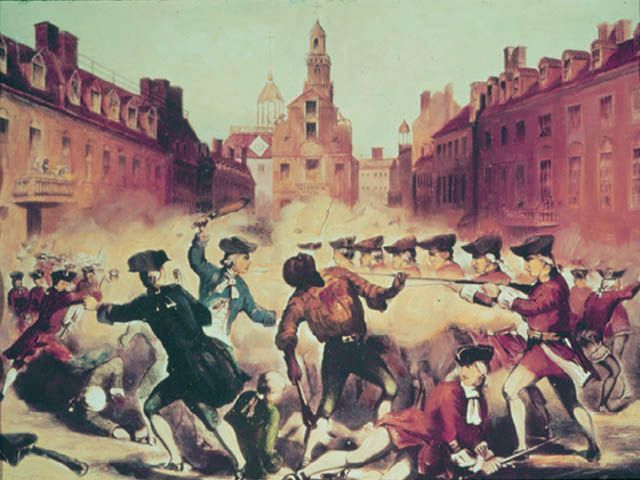

The Boston Massacre, c. 1856, chromolithograph by John Bufford after William L. Champney

Learn More

The Boston Massacre, c. 1856, chromolithograph by John Bufford after William L. Champney

The Boston Massacre, c. 1856, chromolithograph by John Bufford after William L. Champney. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.

This nineteenth century view of the Boston Massacre is obviously based on the Pelham and Revere engravings of 1770, and somewhat resembles the engraving in Nell’s history. In this version, Crispus Attucks is clearly the central figure, shown at the moment he is shot. Boston abolitionists, both Black and white, celebrated Crispus Attucks day – March 5 – for many years prior to the Civil War.

Colored Patriots of the American Revolution

Learn More

Colored Patriots of the American Revolution

Colored Patriots of the American Revolution, William Cooper Nell, 1856. Courtesy of Howard University, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center.

William Cooper Nell’s book and pamphlet were the first publications gathering together the names and stories of Black patriots.

General Francis Marion Inviting A British Officer to Dinner

Learn More

General Francis Marion Inviting A British Officer to Dinner

General Francis Marion Inviting A British Officer to Dinner, engraving by J.N. Gimbrede after painting by John Blake White, 1845. Anne S.K. Military Collection, Brown University Library

This mid-19th century engraving of an earlier painting shows General Francis Marion, the “Swamp Fox” of South Carolina and representations of others who served under him. Two Black men, one preparing food and the other tending a horse are included in the scene. Marion waged a guerrilla war in the southern theater of operations during the American Revolution. Both free and enslaved Black men served in combat roles in Marion’s forces.

The Battle of Cowpens

Learn More

The Battle of Cowpens

The Battle of Cowpens, William Ranney, 1845. Courtesy the Collection of the State of South Carolina

Artist William Ranney’s narrative picture shows the American cavalry commander William Washington (on white horse) as he tangles with the British cavalry leader Banastre Tarleton (on black horse) at the end of the January 17, 1781 battle. At the moment depicted, the Black trumpeter with a gun on the far left saves Washington by wounding the British officer who was about to attack him (to Tarleton’s right).

The Passage of the Delaware, Thomas Sully, 1819

Learn More

The Passage of the Delaware, Thomas Sully, 1819

The Passage of the Delaware, Thomas Sully, 1819. Courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Nearly a half century after the event, Thomas Sully painted a romantic version of Washington, attended by several horsemen, apparently having crossed the Delaware on the way to Trenton. One of Washington’s attendants is Black.

Washington Crossing the Delaware

Learn More

Washington Crossing the Delaware

Washington Crossing the Delaware, 1851, Emmanuel Leutze. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Thirty-two years after Sully, Emmanuel Leutze painted his monumental image of Washington in a boat on the way across the Delaware River. Among the oarsmen is a Black man long identified as Prince Whipple, an enslaved Portsmouth, New Hampshire, man who may actually have been an African prince, according to William Cooper Nell. Nell was incorrect in identifying the oarsman as Whipple. Although Prince Whipple did serve in the Revolution, and fought in several battles, he was not at Trenton with George Washington. Emmanuel Leutze completed his original canvas in Germany in 1851, five years before the publication of Nell’s book. This image is now an icon of American history, and the figure of the Black oarsman is emblematic of many long-forgotten patriots.

Photograph of Holdridge Primus, grandson of Dr. Primus

Learn More

Photograph of Holdridge Primus, grandson of Dr. Primus

Photograph of Holdridge Primus, grandson of Dr. Primus. Courtesy of the Connecticut Historical Society, Photograph of Holdridge Primus, 1983.27.1.

Doctor Primus was a Revolutionary War soldier from Connecticut who, after the war became one of the first professionally trained Black doctors. He learned his profession as an apprentice to his enslaver, Dr. Alexander Wolcott of Windsor, Connecticut. Literate, he signed his name on his manumission documents “Dr. Primus Manumit.” Over the next three generations the Primus family attained middle class status and education, founding the Primus Institute in Talbot County, Maryland to educate newly free people following the American Civil War.

In a letter to her parents in 1867, Rebecca describes her new school:

“We are now building a schoolhouse 34 by 24 ft. which is expected to be completed by the first of October. It is of wood & is being fitted up as comfortably & nicely as other schoolhouse. It will probably cost a little of $400.00. We’ve already paid over $300.00 & $200.00 of this sum were furnished us by our Hartford friends & sympathizers. The recipients know not how to fully express their gratitude for this munificent gift. They are all just beginning life as it were for many of them were made free by the Emancipation Act-for which they revere the name of “Abraham Lincoln.” But they are industrious, & hopeful of the future, their interest in the school is unabated & many of them deny themselves in order to sustain it.”

Rebecca later returned to Hartford and married. She continued to teach at the Talcott Street Church school.

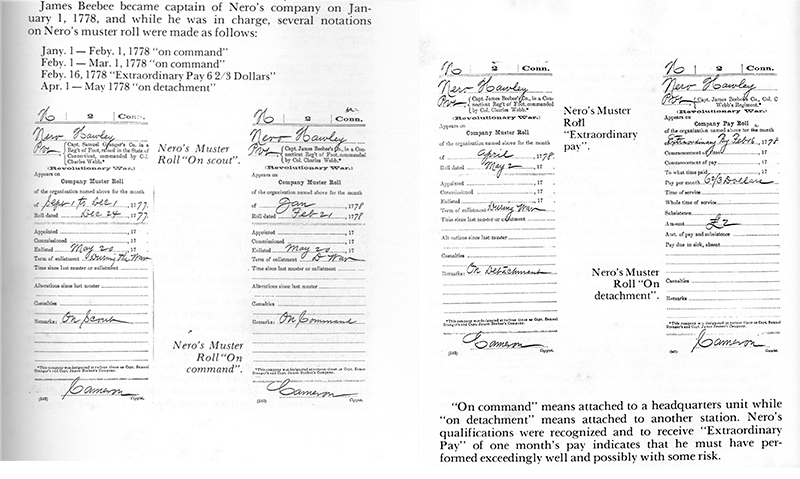

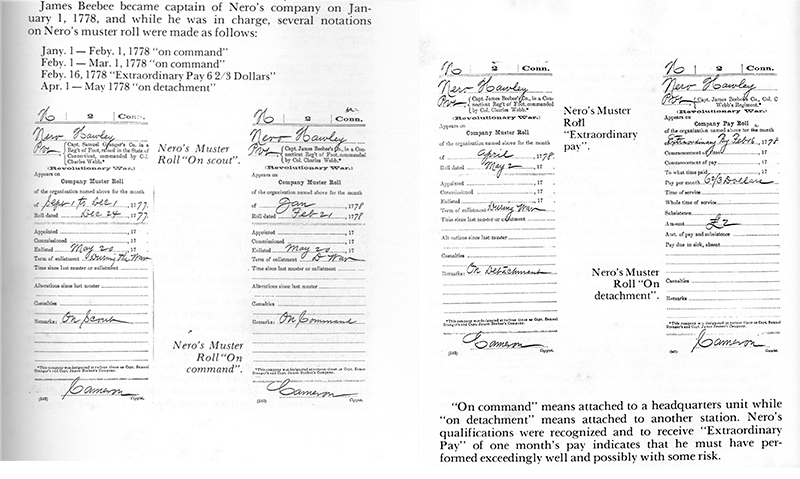

Ancestor’s Service Record for Nero Hawley

Learn More

Ancestor’s Service Record for Nero Hawley

Ancestor’s Service Record for Nero Hawley. Courtesy of Hugh B. Price, Hugh B. Price, President and CEO of the National Urban League: 1994–2003, Great-great-great-great grandson of Nero Hawley.

When James and Augustus Hawley applied for membership in the Sons of the Revolution in the State of Connecticut, they filled out their ancestor’s service, detailing Nero Hawley’s military career.

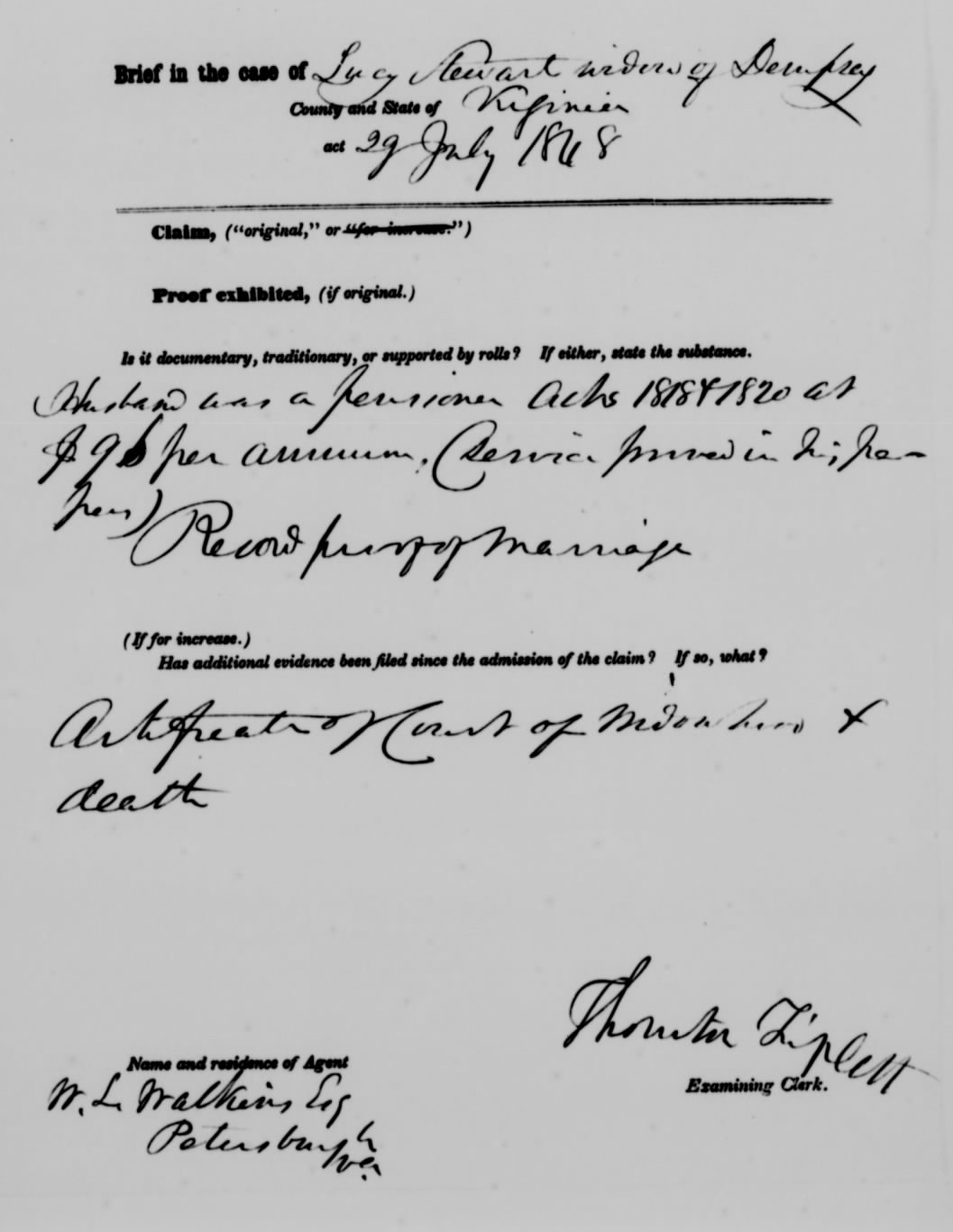

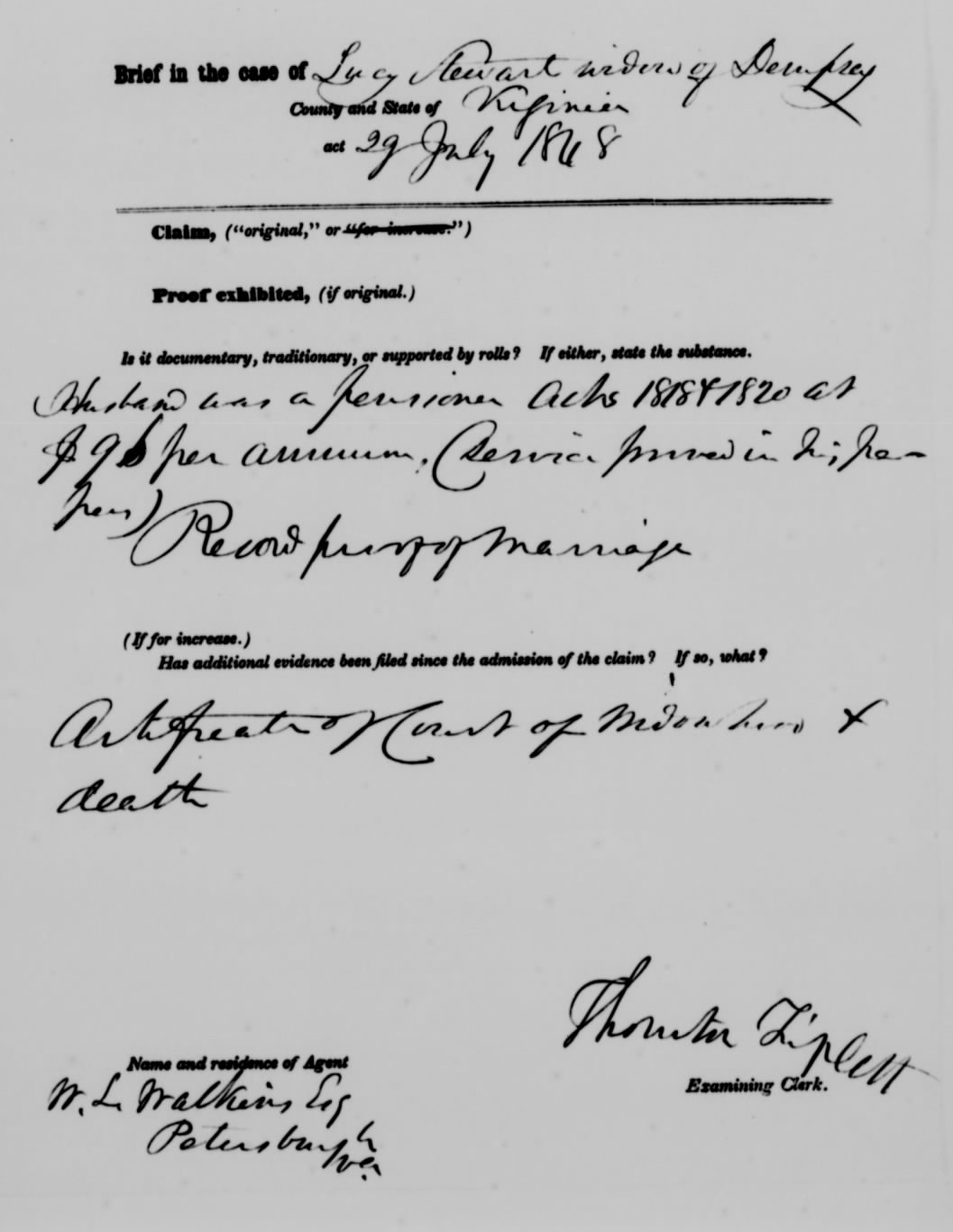

Widow’s Pension Certificate

Learn More

Widow’s Pension Certificate

Widow’s Pension Certificate. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

Dempsey Stewart was a free Black man who enlisted in the 1st North Carolina Regiment for a period of eighteen months. After the war, he lived in Greensville County, Virginia where he married Lucy Berry. They settled in Brunswick County, Virginia, where they purchased at least 144 acres of land. At the time of his death in 1848, his two daughters were living in Indiana. He left his Brunswick County farm to John Stewart, who was to care for Dempsey’s widow Lucy.