Remembrance of Noble Actions

Stories

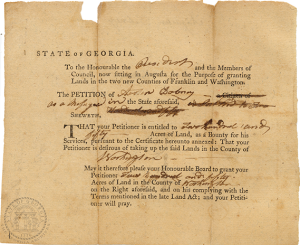

Veterans of the Revolutionary War were entitled to free property. Bounty land, given as a reward for service to one’s country in time of war, was an incentive to enlist. The Virginia General Assembly also offered one enslaved African or enslaved African American to those who enlisted. The Continental Congress established bounty land as part of the “State Quotas for Troops” of September 16, 1776. This act specified the amounts of money as well as the acreage of land to be given as bounty to each man who enlisted in the Continental Army.

Both Congress and individual states offered bounty land, and a veteran could be entitled to both. The amount of land one could receive for his service depended upon his rank in the military. Establishing one’s eligibility often proved difficult, and many soldiers and soldiers’ widows found their bounty land applications denied.

A widow had to prove that she was married to the veteran. This required documents, such as marriage bonds. Black and Native American people were less likely to have these documents. Veterans who were enslaved and freed as a result of their military service might have no records at all, especially if they were married during their enslavement.

Where did the free land come from? Most bounty lands came from areas claimed by the nascent United States and taken from Native Americans in the western “reserves” or the western part of newly formed states. The western reserves encompassed vast lands. The Mitchell Map, used at the Treaty of Paris in 1783, shows the boundaries of the states extending across the North American continent. All veterans, Black, Native American, as well as white, could be given land at the expense of Indigenous nations, some of whom fought alongside the revolutionaries.

Georgia land grant to Austin Dabney. Courtesy of the Georgia Archives, RG 3-4-5, ah00010Austin Dabney, manumitted by Georgia’s government, was granted 250 acres of land as a bounty for his services in the Revolution.

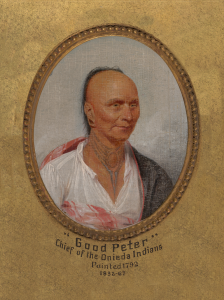

The State of New York awarded Hanyere Tewahangarahken, an Oneida head warrior, three separate lots for a total of 1800 acres as a bounty for his service during the war. A hero of the Battle of Oriskany, he was commissioned a captain in the Continental Army and served for the duration of the war. In a few short years after the date of this bounty, the Oneida Nation’s land had been taken by or sold to white property owners.

The voice of the birds from every quarter cried out “You have lost your country– You have lost your country– You’ve lost your country! You have acted unwisely, and done wrong.” And what increased the alarm was that the birds who made this cry were white birds. Good Peter, 1792

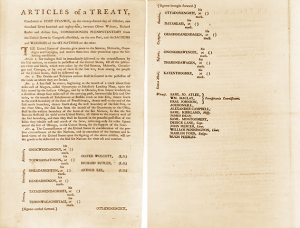

Four of the six nations of the Haudenosaune fought on the side of the British, but the Oneidas and the Tuscaroras fought beside the Americans. It is important to recognize that members of each nation made their own decisions and some chose to fight counter to the officially stated alliance of their nation. At the end of the war, a series of negotiations and treaties between the United States and the Oneidas, beginning with the Treaty of Fort Stanwix in 1784, were to have safeguarded the Oneida lands for all time. The terms of the treaty were re-affirmed in 1789 and culminated in 1794 with the Treaty of Canandaigua. No other treaties were to be contracted without the consent of Congress. However, the state of New York acquired most of the Oneida lands through lease and purchase. Most of the Oneida Nation, due to harassment from American settlers, were forced to leave the region for lands in Wisconsin.

Treaty of Fort Stanwix, 1784. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.The Treaty of Paris of 1783 that ended the war with England made no provision for the Native American combatants. The Treaty of 1784 at Stanwix, between the United States and the Haudenosaunee, ended hostilities between the United States, its allies the Oneidas and Tuscaroras, and the four nations that sided with the British, the Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga, and Mohawk. Representatives of all six nations signed the treaty.

Guy Johnson’s map of Indian lands. Courtesy of the New York Public LibraryGuy Johnson drew this map for the British governor of New York, William Tryon. On it he located the Six Nations of the confederacy: the Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida, Mohawk, and Tuscarora. Most of these nations felt a deep loyalty to Sir William Johnson, who died in 1774, and subsequently to members of his family. They were also motivated by complicated and sometimes conflicting incentives, including land and economics. The Treaty of Fort Stanwix confirmed the possession of the lands of the Oneidas and Tuscaroras, and drew new boundaries for the other four nations, the Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga, and Oneida.

Portrait of Good Peter, John Trumbull, 1792. Courtesy of Yale University Art Gallery, Trumbull Collection.Oneida Chief Good Peter learned that New York Governor George Clinton and others were gradually taking the Oneida’s land in the name of saving it. Good Peter brought the case to the State of New York which conveniently decided that Clinton and others had purchased the land thereby dispossessing the Oneidas.

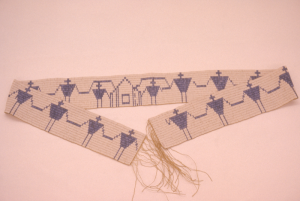

Reproduction wampum belt. Photograph courtesy of the Carnegie Museum.Belts of shell beads, called wampum, were used to seal contracts by both Native nations and colonial governments. The original belt, called the “George Washington Covenant Belt,” was commissioned by the new United States government and is believed to have sealed the Canandaigua Treaty of 1794. The original is in the custody of the Onondaga Nation.

Annuity Cloth. Courtesy of the Oneida Indian Nation.

The Treaty of Canandaigua was signed November 11, 1794 between the United States and member nations of the Haudenosaunee (“Iroquois”) Confederacy. Over 200 years later, the treaty, like the U.S. Constitution, remains a living document. Though the agreement has been strained and terms of the treaty violated, its ideals are still upheld: the promise of friendship, peace, and lasting recognition of Native American sovereignty between the nations. There are commemorations in Canandaigua, New York, held each year by the Haudenosaunee people to mark the anniversary of the treaty. As a symbol of the tangible bond between the nations, the United States sends the Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida, Mohawk, and Tuscarora bundles of annuity cloth, like the ivory muslin here. Oneida Members for generations have accepted their pieces of “treaty cloth,” and it is still disbursed annually to the population of about 1,000 Oneidas in New York.

The message of freedom and equality as expressed in the Declaration of Independence was not lost on the free Black, enslaved, and Native American people who lived through the American Revolution. As early as 1773, enslaved people in Massachusetts were pointing out the irony of slave-owning colonists fighting for their own freedom: “We expect great things from men who have made such a noble stand against the designs of their fellow-men to enslave them.” Lemuel Haynes wrote an essay, “Liberty Further Extended,” in which he argued the case for the abolition of slavery as a natural outcome of the Revolution: “I think it not hyperbolical to affirm, that Even an affrican (sic), has Equally as good a right to his Liberty in common with Englishmen.”

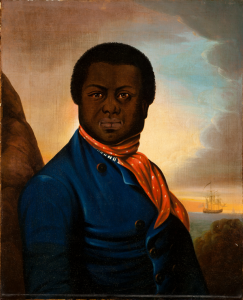

Portrait of a Sailor (Paul Cuffe?), c1800 Courtesy Los Angeles Museum of Fine ArtIn 1780, Paul Cuffe and other freemen in Dartmouth, Massachusetts, petitioned the court for relief from paying taxes, citing the colonists’ fight against taxation without representation, they wanted voting rights for themselves. This event contributed to Massachusetts granting voting rights to all free male citizens of the state in 1783.

Elizabeth Freeman in 1781 and Quock Walker in 1783, sued for their freedom arguing the principles of the American Revolution and the Massachusetts Constitution of 1780’s phrase that all men are “born free and equal.” These cases lead to the end of slavery in Massachusetts in 1783.

Elizabeth Freeman miniature portrait by Susan Anne Livingston Ridley Sedgwick, 1811, Courtesy of the Collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society

Elizabeth Freeman miniature portrait by Susan Anne Livingston Ridley Sedgwick, 1811, Courtesy of the Collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society

Crispus Attucks

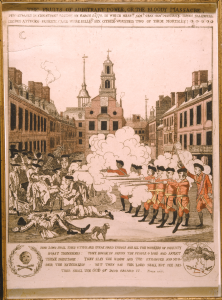

As the gun smoke cleared on March 5, 1770, five men lay dead, among them was Crispus Attucks. Images of the “Boston Massacre” were available for sale on the city’s streets almost immediately after the event took place. Paul Revere, silversmith and engraver, published his version of the “bloody massacre” after copying an engraving by Henry Pelham only twenty-one days after the event. Pelham’s engraving was published after Revere’s and is nearly identical. Neither shows a Black man among the dead and wounded. Attucks is described in contemporary accounts as mulatto. Crispus Attucks’ mother was Native American, a member of the Massachuset Nation, and his father is believed to be African.

Reproduction of The Bloody Massacre, by Henry Pelham. Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society

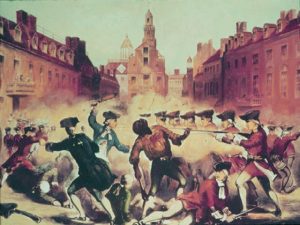

The Boston Massacre, c. 1856, chromolithograph by John Bufford after William L. Champney. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.

This nineteenth century view of the Boston Massacre is obviously based on the Pelham and Revere engravings of 1770, and somewhat resembles the engraving in Nell’s history. In this version, Crispus Attucks is clearly the central figure, shown at the moment he is shot. Boston abolitionists, both Black and white, celebrated Crispus Attucks day – March 5 – for many years prior to the Civil War.

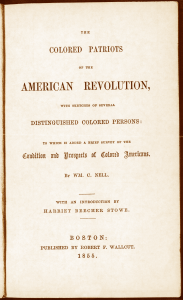

Colored Patriots of the American Revolution, William Cooper Nell, 1856. Courtesy of Howard University, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center.

William Cooper Nell’s book and pamphlet were the first publications gathering together the names and stories of Black patriots.

Many nineteenth century artists included Black people or Native people in their heroic depictions of the events of the American Revolution.

General Francis Marion Inviting A British Officer to Dinner, engraving by J.N. Gimbrede after painting by John Blake White, 1845. Anne S.K. Military Collection, Brown University LibraryThis mid-19th century engraving of an earlier painting shows General Francis Marion, the “Swamp Fox” of South Carolina and representations of others who served under him. Two Black men, one preparing food and the other tending a horse are included in the scene. Marion waged a guerrilla war in the southern theater of operations during the American Revolution. Both free and enslaved Black men served in combat roles in Marion’s forces.

The Battle of Cowpens, William Ranney, 1845. Courtesy the Collection of the State of South CarolinaArtist William Ranney’s narrative picture shows the American cavalry commander William Washington (on white horse) as he tangles with the British cavalry leader Banastre Tarleton (on black horse) at the end of the January 17, 1781 battle. At the moment depicted, the Black trumpeter with a gun on the far left saves Washington by wounding the British officer who was about to attack him (to Tarleton’s right).

The Passage of the Delaware, Thomas Sully, 1819. Courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.Nearly a half century after the event, Thomas Sully painted a romantic version of Washington, attended by several horsemen, apparently having crossed the Delaware on the way to Trenton. One of Washington’s attendants is Black.

Washington Crossing the Delaware, 1851, Emmanuel Leutze. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Thirty-two years after Sully, Emmanuel Leutze painted his monumental image of Washington in a boat on the way across the Delaware River. Among the oarsmen is a Black man long identified as Prince Whipple, an enslaved Portsmouth, New Hampshire, man who may actually have been an African prince, according to William Cooper Nell. Nell was incorrect in identifying the oarsman as Whipple. Although Prince Whipple did serve in the Revolution, and fought in several battles, he was not at Trenton with George Washington. Emmanuel Leutze completed his original canvas in Germany in 1851, five years before the publication of Nell’s book. This image is now an icon of American history, and the figure of the Black oarsman is emblematic of many long-forgotten patriots.

The Boston Massacre, c. 1856, chromolithograph by John Bufford after William L. Champney. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.

The Boston Massacre, c. 1856, chromolithograph by John Bufford after William L. Champney. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.