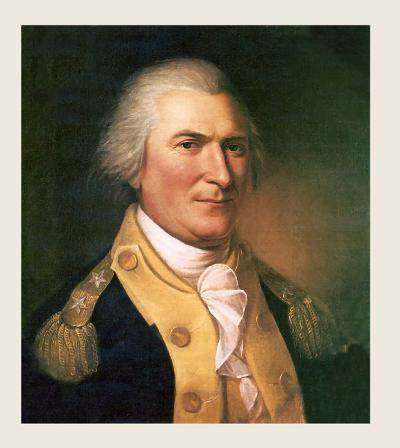

At the outset of the American Revolution, St. Clair supported the cause for independence and accepted a commission in the Continental Army as a colonel in the 3rd Pennsylvania Regiment. St. Clair was with Washington as he crossed the Delaware and is credited with the strategy that led to Washington’s capture of Trenton and Princeton.

St. Clair was promoted to major general and sent to defend Fort Ticonderoga. Realizing that his troops were greatly outnumbered, he ordered a strategic retreat. He faced court martial but was exonerated and returned to duty joining Washington at Valley Forge. St. Clair served another eight years and was at Washington’s side for the British surrender at Yorktown and at his inauguration as the first President of the United States.

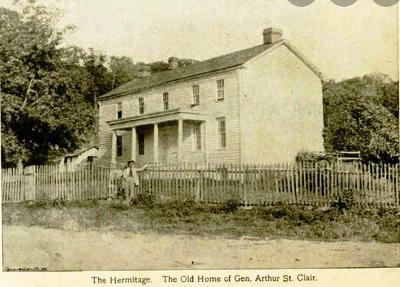

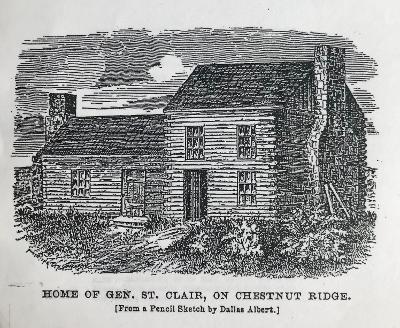

At the end of the War, St. Clair was elected the seventh President of Congress under the Articles of Confederation. He served as the first Governor of the Northwest Territory from 1788 to 1802 and then returned to private life. He was never repaid the vast sums he extended to care for his troops during the War. In debt, he had a sheriff’s sale of his land and holdings and spent the remainder of his life in poverty relegated to a humble log cabin on a ridge nearby his former estate.

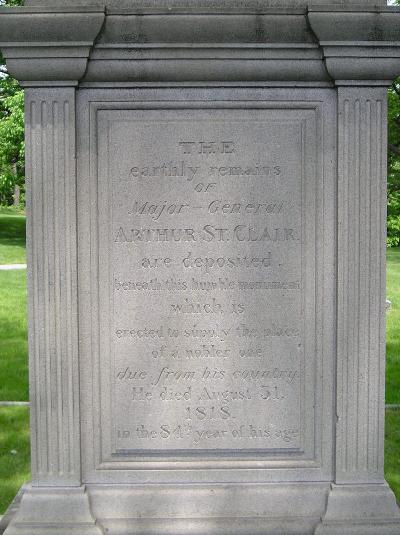

St. Clair died on August 31, 1818, at Laurel Hill, Somerset County, Pennsylvania, virtually forgotten. Years later a monument “befitting a soldier of the Revolution” was erected at his gravesite.

Ohio Congressman Elisha Whittlesey visited St. Clair in the waning years of the General’s life and shared his observations in correspondence to a friend:

“I never was in the presence of a man that caused me to feel the same degree of veneration and esteem. He wore a citizen’s dress of black of the Revolution; his hair clubbed and powdered. When we entered he arose with dignity and received us most courteously. His dwelling was a common double log house of the western country, that a neighborhood would roll up in an afternoon. Chestnut Ridge was bleak and barren. There lived the friend and confidant of Washington, the ex-Governor of the fairest portion of creation. It was in the neighborhood, if not the view, of a large estate at Ligonier that he owned at the commencement of the Revolution, and which, as I have at times understood, was sacrificed to promote the success of the Revolution. Poverty did not cause him to lose self-respect; and were he now living his personal appearance would command universal admiration.”