Section 1 of the Virginia Declaration of Rights: “That all men are by nature equally free and independent and have certain inherent rights, of which, when they enter into a state of society, they cannot, by any compact, deprive or divest their posterity; namely, the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the means of acquiring and possessing property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety.”

Written by George Mason; adopted by the Virginia Constitutional Convention on June 12, 1776.

These sentiments have been reflected worldwide in Thomas Jefferson’s “Declaration of Independence” and later echoed in the Marquis de Lafayette’s 1789 “Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen.”

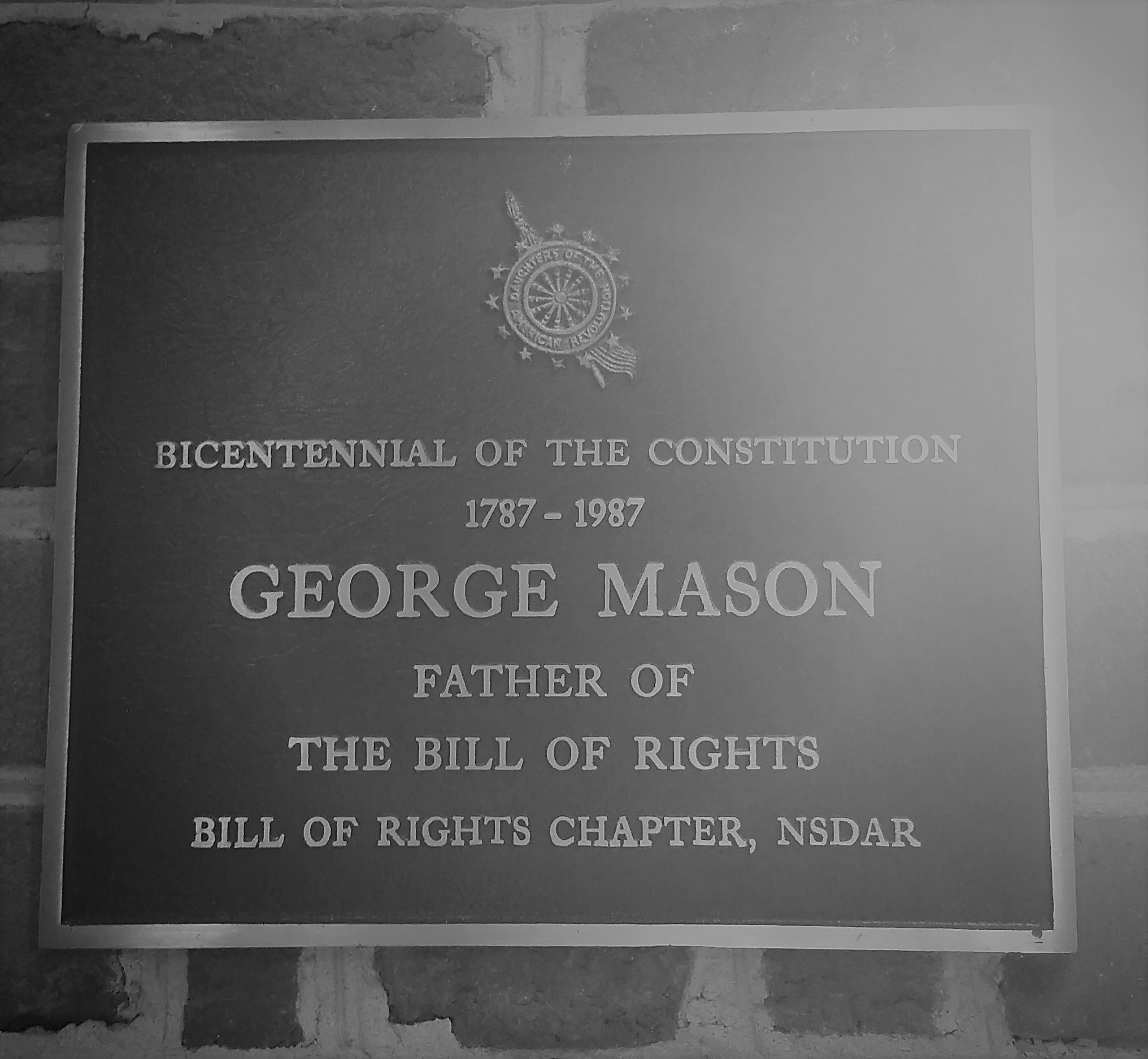

Mason earned the respect of many serving as a delegate at the 1787 Continental Convention in Philadelphia and was a key voice on the Grand Committee that developed “The Great Compromise,” which resolved the conflict between the larger and smaller states. However, his staunch belief in the absolute necessity for a bill of rights caused friction at the Convention when he refused to sign the Constitution—primarily because it did not contain a declaration of rights. He returned home under a cloud, and even his friendship with George Washington suffered.

Following Virginia’s ratification of the Constitution on June 25, 1788, Mason served on a committee which compiled a list of amendments to be adopted. He believed that with the proper amendments the Constitution could be “a fine instrument of government.” His dear friend, James Madison, presented the amendments to the new Congress on behalf of Virginia.

The Bill of Rights to the Constitution of the United States of America was ratified on December 15, 1791, and Mason died at home less than a year later, on October 7, 1792. He can rest in peace knowing that his fight for a Bill of Rights for our nation was secured.