He was a member of the Stamp Act Congress of 1765, also known as Continental Congress, which confirmed his independent sentiment on the colonists’ side against the British.

The Stamp Act Congress was the first colonial action against imperial taxation issued by the British Parliament, as colonial residents were required to purchase a stamp with silver or gold. The stamp was to be used on all documents, even newspapers, pamphlets and cards. The repealed act was ultimately unenforceable due to colonial resistance.

In 1766, he was elected to the Massachusetts House of Representatives, where he benefitted from the support of Samuel Adams, a leader of Boston’s “Whigs” or “Patriot” party.

In 1768, his merchant sloop Liberty was impounded by customs at Boston Harbor, accused of running contraband wine. British officials filed two lawsuits against him, and confiscated his ship, later burned in Rhode Island. The lawsuits were dropped, but this led to his support of the Boston Tea Party, and the next year, he addressed the public in Boston, commemorating the Boston Massacre.

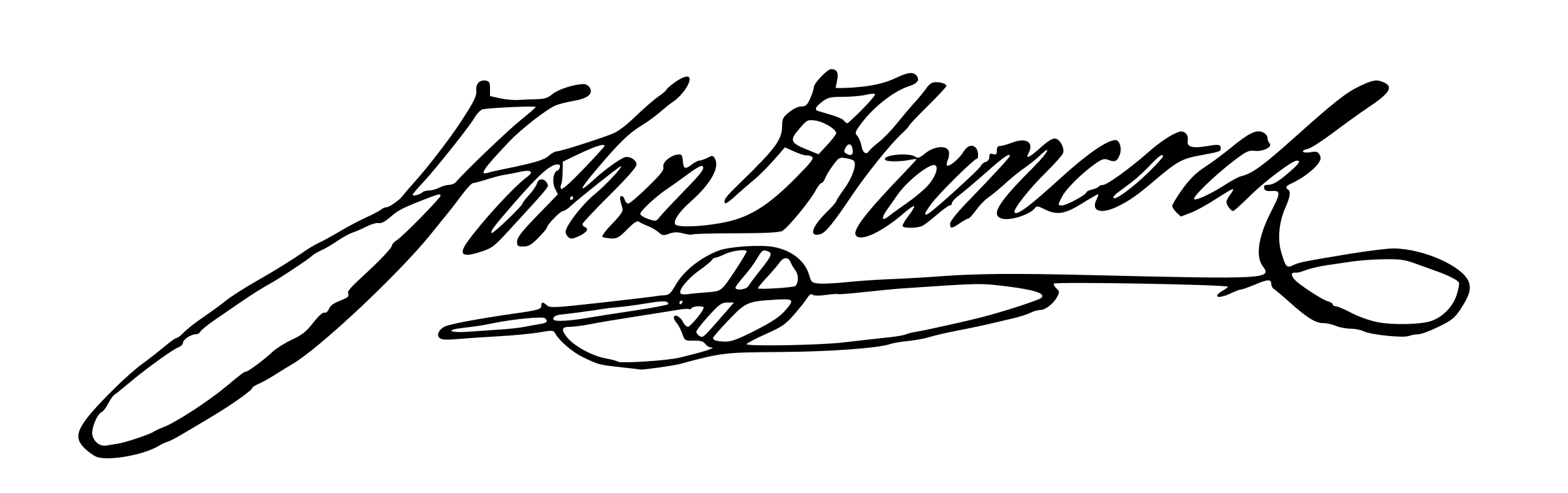

He was elected to Continental Congress in 1774, and served as President of the Second Continental Congress in 1775. His presidency coincided with the adoption of the Declaration of Independence and his large, recognizable signature was the first to be written. The significance of it has led to an understanding that a “person’s signature” is his “John Hancock.”

In 1780, he was elected the first Governor of Massachusetts and served for five years. In 1787, even though suffering from gout, he was elected to the same position again as the third governor, and served until his death in Boston on October 8, 1793.